Movie Review: Better Luck Tomorrow — Is This the Prequel to The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift?

Four Asian high school honor students take on illegal extra-curricular activities in Justin Lin’s BETTER LUCK TOMORROW. What starts with cheat sheets quickly escalates to major criminal activities, while our main character Ben starts using cocaine to keep up his grades and gang status.

Four Asian high school honor students take on illegal extra-curricular activities in Justin Lin’s BETTER LUCK TOMORROW. What starts with cheat sheets quickly escalates to major criminal activities, while our main character Ben starts using cocaine to keep up his grades and gang status.

The high school drama feels honest, with Ben taken with lab partner Stephanie, unsure of his place in the high school hierarchy, and very focused on college and his future. In fact, for the first act of this film I thought that’s all the movie would be–an Asian-American coming of age drama like The Breakfast Club or Almost Famous. When the film takes its second act turn and becomes a crime film it was unexpected, but never felt disingenuous.

I kept trying to anticipate how the film would progress, and I never got it right. Lin’s picture (which he co-wrote) keeps taking unexpected turns, and I was along for the ride.

The cast is uniformly awesome. Shen, likely best known now for his three turns in the Hatchet series, carries the film. Told from his point of view, he’s in every scene. His daily routines reminded me of an Aaronofsky character, but showed his focus on his goals. When the character makes unexpected choices, it’s Shen who makes sense of it.

Jason Tobin plays Virgil. Seemingly the least intelligent and most impulsive member of the gang, Tobin brings a madness and pathos to the role that really added suspense. It really seems Virgil will be the group’s undoing.

Roger Fan’s Derec, the leader of the gang, is charismatic and scheming, but also seems like a good guy. The wrong balance with Derec could turn you against the gang, but Fan plays the balance and even at times seems vulnerable.

And Sung Kang plays Han–the reason I watched this film. Kang would go on to play Han in 3 of Lin’s FAST AND FURIOUS films, and Lin has said it’s the same Han seen in this film. Here Han is not given the focus much, but he is the coolest member of the gang with a pretty nice car. He’d fade into the background were it not for his future collaborations with Lin.

And in a supporting role is the film’s biggest star, John Cho. Primarily known as the “MILF Guy” from American Pie, of course Cho would go on to do the Harold and Kumar films before playing Sulu on Star Trek. Here, as a spoiled rich kid two-timing Stephanie, the object of Ben’s affections, Cho strikes the right notes with a tricky and pretentious character.

The film avoids any stereotypes–these are just high schoolers who happen to be Asian, but they’re all-American kids balancing a bright future with a life of crime and instant gratification.

When the film ended I found myself satisfied. It was a drama film that had elements of crime, not a crime film with elements of drama, but an entertaining and moving watch. RECOMMEND.

March 10, 2015 Posted by Arnie C | Movies | Crime, Drama, Film, Gangster, Han, Justin Lin, Movie, Prequel, Sundance, Teenager, the fast and the furious | Comments Off on Movie Review: Better Luck Tomorrow — Is This the Prequel to The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift?

The 40 Year-Old-Critic: Requiem for a Dream (2000)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

Have you ever seen a film that you instantly loved, but never wanted to see again? That was my reaction to seeing Requiem for a Dream in 2000.

I was drawn in by director Darren Aronofsky. I had seen his first film, the black-and-white techno thriller Pi, and was enthralled. The use of music, the sophisticated themes, the weird camera angles, the ideas of patterns in everything in life, the repeated sequences that formed a pattern in a movie itself about patterns; all of it left me entranced. I instantly knew Aronofsky was a talent to watch.

I anxiously awaited Requiem’s release, my excitement growing as I read high praise coming out of its screening at the Cannes Film Festival. Being a small film ($4.5M budget) with a very non-commercial NC-17 rating, I knew Requiem would not get a wide release. Sure enough, the picture opened on just 93 screens.

Like a character in an Aronofsky film, I was obsessed with seeing this movie. As such I made plans to visit my Now Playing Podcast co-host Stuart in Chicago, and there we would go see Requiem together.

Burstyn and Leto share a rare scene together in Requiem for a Dream.

Based on the novel of the same name by Hubert Selby, Jr., the film follows nine months in the lives of Harry Goldfarb (Jared Leto) and his mother Sara (Ellen Burstyn). Despite the familial relation, the two characters rarely interact; their stories run parallel as we follow their hopes and falls. Starting in “Summer” and ending in “Winter”, the falling temperatures also represent the decline in the characters’ fortunes.

Harry is a heroin addict. He and his friend Tyrone (Marlon Wayans) have hit bottom so many times that stealing Sara’s television to pawn for drug money has become routine. After one theft, followed by a good high at the beginning of the film, Tyrone starts to show ambition –rather than just shooting up, the friends decide to resell some of their drugs to double their money. They have career aspirations of someday dealing a full pound of pure heroin that would set them up for a long time and allow Tyrone to move out of his bad neighborhood.

They start their plan — taking regular pauses to shoot up — and things start to go well. Harry even earns enough money to try to make amends with his mother, and buys her a new, modern television.

In addition to Harry’s burgeoning career as a drug dealer, he is madly in love with girlfriend and fellow junkie, Marion (Jennifer Connelly). The two dream of using their drug money to open a clothing store, allowing Marion to escape her controlling parents. With his money and his girl, things look great for Harry.

Sara, meanwhile, is also finding success. When the film begins she is an elderly widow living alone in an apartment, with little to do but watch self-help television shows. One day her fortune changes with a single phone call: she has been selected to be on her favorite game show. Sara is beyond excited, but also nervous about appearing on national television. A neighbor helps her dye her hair, with unfortunate results. She’s even more distressed after finding out the red dress she wants to wear on the show — one her late husband loved — no longer fits.

Sara starts popping the pills faster and faster to fit in that red dress.

After attempts at crash dieting prove unsuccessful, Sara visits a doctor and begins taking a heavy dose of diet pills. The amphetamines have severe side effects — Sara starts to grind her teeth and can’t sit still — but she loses 25 pounds and feels great. Her looming television appearance has made her the superstar among the retirees in her apartment building and she’s soaking it up.

When Harry brings his mother the new television he instantly knows Sara is tweaking on uppers. He tries to get her to stop, but she is too excited for the game show; even though her obsessive checking the mail for information about her appearance has yielded no results.

If you haven’t seen Requiem for a Dream, if you’ve only read the description above, you might think this is an ugly movie about despicable people. A heroin addict who steals from his own mother? A lonely old woman obsessed with television? A junkie aspiring to become a dealer? In so many movies these characters would be the villains, or at least the antagonists. But Aronofsky is a deft storyteller, and slowly he makes us care for each person on the screen.

Every character is given a touching moment. For Harry and Marion, it’s them lying in bed expressing their affection for each other. They don’t just say “I love you” — rather Harry uses the trite expression, “You’re the most beautiful girl I’ve ever seen.” She responds, telling him she’s heard that a lot, but adds that when Harry tells her it truly has meaning.

More than words, we see that scene through the points of view of both characters via split-screen, allowing for close-ups of Leto and Connelly. This unique approach drives home multiple points: a) they’re together, yet not, b) it’s the first sign that something will come between them, and c) the close-up shots convey intimacy, not isolation.

Then the shots get more inventive. We see Harry talk on one side of the screen, and on the other we see his hand caressing Marion, his thumb brushing over her lips, her palm. Then we see her close-up, and her hands on him. It’s not a sex scene, but this communion between two characters shows their relationship in a much more intimate setting. After only two minutes you want these kids to make it, yet their addiction hangs like a storm cloud.

The same goes for Harry and his mother. While he starts by stealing her television, causing Sara to lock herself in a closet away from her son, he still tries to assure her that everything will be okay. Later in “Summer” we see Harry and Marion on the beach, the man verbalizing how much he loves and cares for his mother and how, now that he has money, he wants to make right every wrong he’s done. It’s a deft turn, but thanks to Leto’s performance and earnest language, Aronofsky has made this thieving drug abuser actually seem noble and good.

Harry and Tyrone take in some TV.

Tyrone is given the least background of the four, an odd choice considering he is the lead drug dealer. His girlfriend is never named, and his backstory is limited to a bit about honoring his dead mother. Still, Wayans gives a career-best performance in a rare, non-comedic role for the Scary Movie actor. Much of this is due to Aronofsky’s editing — one needs only to watch the deleted scenes on the DVD to realize Wayans tried multiple approaches to Tyrone, including a full-on Jar Jar Binks impersonation.

As shown on screen, Tyrone is the least developed character, yet still a likable personality thanks to the heart Wayans puts into the role.

It’s actually astounding that Requiem makes drug dealing seem like a bright, hopeful career path.

As for Sara, this character may not be one you hate, but one you pity. A virtual shut-in with a television obsession, it is again the script and the actress that makes Sara sympathetic instead of just pathetic. When Harry comes to tell his mother about the new television he asks why she cares so much about the game show appearance.

She responds at first by pointing out to Harry the reverential treatment she has been getting from the other biddies in her building:

“I’m somebody now, Harry. Everybody likes me. Soon, millions of people will see me and they’ll all like me. I’ll tell them about you, and your father, how good he was to us. Remember?”

Then after a pause, an even sadder truth comes out — this television show is all she has to live for.

“It’s a reason to get up in the morning. It’s a reason to lose weight, to fit in the red dress. It’s a reason to smile. It makes tomorrow all right. What have I got, Harry? Why should I even make the bed or wash the dishes? I do them, but why should I? I’m alone. Your father’s gone. You’re gone. I’ve got no one to care for. What have I got, Harry? I’m lonely. I’m old.”

Sara hallucinates a visit to her favorite TV show, hosted by Tappy Tibbons (Christopher McDonald in a memorable minor role).

The obvious answer is right there: Harry could pay more attention to his mother. What she really needs isn’t another television, it’s human connection. But while Harry is desperately trying to be a good son he’s exacerbating his mother’s issue by allowing her to submerge deeper into television, versus helping her to escape it. Despite seeing his mother’s obvious bad reaction to the uppers, this is the last time Harry sees her.

Even with the obvious, unspoken truth of the scene, the monologue could have fallen flat if not for Burstyn’s amazing performance. She jitters while she plays the scene, expressing her agitation from the pills, with a nervousness at being so honest with anyone. She says the lines with a smile, but the sadness comes through in the delivery. Burstyn deserves every accolade she was given for this performance.

Finally, the mood is lightened with humor. When Harry and Tyrone steal the television it’s a joy watching them wheel it past all of Sara’s neighbors, who are more concerned with soaking up the afternoon sun than they are the obvious and strange theft. The characters laugh, joke, and keep the film from becoming too morose.

The combination of the amazing director, actors, and screenplay prevent this story from feeling trite or ugly. When “Summer” ends I was rooting for all four characters to achieve their dreams.

But if that was the summer, soon must come the fall, literally and metaphorically.

For Sara, this comes from her body building up a resistance to the amphetamines. She no longer gets her high from the pills, and though her red dress nearly fits, she needs to continue losing weight. When the doctor won’t up the dosage she self-medicates, taking multiple pills at once.

For Harry, Marion, and Tyrone, their downfall begins when a drug war breaks out in the city. Supplies of heroin have dried up — they can’t get any more to sell, and they can’t get any more to take. Their relationships are stressed, especially by Marion, who seems to suffer the worst withdrawal and blames Harry for her inability to shoot up.

By the time the film gets to “Winter” the movie is no longer a dark comedy. Each character becomes more desperate, and their ends are each so awful that Requiem for a Dream practically becomes a horror film. Yet none of it would work had we not cared for the characters — we would have applauded horrible people getting their just desserts. That I love these people and don’t want to see their ruination is the result of successful, manipulative storytelling of the best possible sort. Aronofsky made me like them, then pulled the rug out from under them — he did the same to us in the audience.

When I left the theater I was shaken and sad. The ending was depressing, but it was just; and I realized that. I felt as mournful as I would for a friend who’d gone down a bad road. This movie was hard — hard to watch, hard on its characters, and hard on the audience. I left the theater knowing I loved every frame of this film but also thinking it was such an emotional trial that I never wanted to watch it again.

I did though, many times. Beyond just great storytelling, Requiem for a Dream is a visual masterpiece that I — after some time passed — wanted to revisit to fully take in.

Aronofsky’s second feature brought back so many of the things I’d enjoyed in Pi, especially the inventive, experimental camerawork. Now, more than a decade later in a time when GoPro cameras are strapped to everyone’s heads, you see the genius in Aronofsky’s self-proclamed “Schnoz cam” — strapping the camera to an actor so the person always stays in the center of the frame while the background and scenery move around them. First used in Pi and then in Requiem, this gave the feeling of a character surrounded by a world out of control — a sign of madness, or a visual representation of vertigo. When sped up film footage is added to the effect, you see that Aronofsky created an entirely new way to deliver the same emotion as the old Hitchcockian “push and pull” change of depth.

Sara finally fit in her red dress, but at what cost?

One of the things that impressed me about Pi was its unique visual style. Despite being very low budget, the use of superimposed images, quick cutting, and repetition was hypnotic. That is also on full display in Requiem. Every time the characters get high, be it by snorting, shooting up, or popping pills, a ritual is performed. The film cuts to a montage that lasts only seconds but shows the actions, and the characters. A lighter is lit, drugs boil, a syringe fills, blood courses through veins, pupils dilate. It all happens so fast that it’s virtually subliminal, yet it tells us everything we need to know. As the film becomes more desperate the montages are even faster, showing us people stuck in a cycle of self-destruction.

Aronofsky also isn’t afraid to get surreal. In the depths of psychosis Sara sees cupcakes floating in the air, her favorite self-help TV personality appears in her living room, interlaced at her television’s 480 lines of resolution. At one point her refrigerator even opens a gaping maw to eat her. These types of shots could undermine the mood but, as done here, they just enhance it.

In addition to the camerawork, enough credit simply cannot be given to composer Clint Mansell. I had the CD from Pi, his first film score, on an endless loop in my car; the electronic techno score was perfect for that film about a computer programmer, but I never would have thought the composer could hit the emotional resonance he did when he reteamed with Aronofsky for Requiem.

As this was a low-budget film, the score was performed by just four people: The Kronos Quartet. Still, with just violins, a viola, and a cello this score permeates nearly every frame of the movie. The low, sonorous tones of the cello dominate and make even the happy scenes foreboding. It’s a gorgeous composition that feels so classical it’s impossible to believe it was written in the 21st century; it feels like the work of Edvard Grieg, or one of Beethoven’s darker works.

The score has such an emotional resonance that it has been the breakout star of Requiem for a Dream; even if you’ve not seen this film I guarantee you’ve heard the score’s climactic movement, “Lux Aeterna.” Just two years later, in 2002, my jaw hit the floor when the trailer for Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers was scored to an orchestral version of “Lux Aeterna” — the assemblage of instruments and a faster tempo giving the song a more epic feel than the Quartet did alone (This orchestral version is available for digital purchase at Amazon).

In the years since, “Lux Aeterna” has been a go-to track for movie trailers, including Zathura, I Am Legend, Sunshine, The Da Vinci Code and, unlikely as it may seem, it was even used in Barbie doll ads!

Combined, every element of this film comes together as smoothly as one of Harry’s heroin montages. More, the performances, cinematography, and soundtrack all underscore the film’s thesis — summed up in the title — about the lengths to which people go to try and achieve their dreams. No matter what your dream, be it to be a TV star, a clothing shop owner, a screenwriter, or a podcaster, it’s a plight to which everyone can relate.

Aronofsky finally achieved mainstream success and acclaim with 2008’s The Wrestler, and then went on to even greater success with 2010’s Black Swan. I consider that unfortunate. While I like both of those films, the director has never achieved a more perfect theatrical representation of obsession than he did with Requiem for a Dream. And though I’ve yet to see this year’s Noah, my feeling is Requiem is Aronofsky’s best film to date.

Even if I do have to steel myself every time I rewatch it.

Tomorrow — 2001!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 30, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Music, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 2000s, 40-Year-Old Critic, addiction, Barbie, Darren Aronofsky, dealing, Drama, drugs, Ellen Burstyn, Enertainment, Film, Heroin, horror, Jared Leto, Jennifer Connelly, Lord of the Rings, Lux Aeterna, Marlon Wayans, Movie, Movies, NC-17, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Requiem for a Dream, Review, Reviews, The Two Towers | 2 Comments

40 Year-Old-Critic: Chasing Amy (1997)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

Kevin Smith is a polarizing figure in cinema. The director certainly has his legion of fans, and having attended several conventions with Smith as a featured guest, it seems those fans are mostly male, mostly under 30, and very willing to connect with his characters; lovable losers such as Clerks’ Randall and Dante (Brian O’Halloran and Jeff Anderson, respectively).

I am not in Smith’s camp, and on Now Playing Podcast I have repeatedly expressed my disdain for his body of work.

Yet allow me in this entry of The 40-Year-Old Critic to praise Smith’s best film, 1997’s Chasing Amy.

Amy (as some fans refer to it) was Smith’s third picture. The director was a Sundance phenom with his black-and-white debut (the aforementioned Clerks) in 1994. It did well in theaters and truly found its audience on video — an audience that included me. Thanks to Quentin Tarantino and Reservoir Dogs, I was paying more attention to indie films, especially those heavily promoted by Miramax. As such, I saw Clerks on VHS and enjoyed it.

As I mentioned in my review of Leaving Las Vegas, around this time in my life I was underemployed and frustrated with my lack of career options, so I related heavily to Dante in Clerks. Plus, I was enraptured by the raunchy jokes. Smith raised the bar on profanity with language that originally earned his film an NC-17 rating. As I did with Beverly Hills Cop before it, I laughed loud and hard at Clerks’ envelope-pushing comedy.

Smith parlayed that success into a studio picture, 1995’s Mallrats. The director spent $6 million of Universal Studios’ money on a movie that barely made one-third that amount. Even as a fan of Clerks I thought Mallrats was too cartoonish, too broad. With new lead duo Brodie Bruce and T.S. Quint (Jason Lee and Jeremy London, respectively), Mallrats tried to replicate the bromance of Clerks in a way that felt forced. More, it seemed Smith’s signature characters of Jay (Jason Mewes) and Silent Bob (Smith himself) would not work in color.

Mallrats would not be Smith’s last failure, but it may be his most fortuitous. First, it established his relationship with Ben Affleck, who had a minor role. Second, after Mallrats Smith returned to his “comfort zone” of small, indie filmmaking. On a $250,000 budget — extraordinarily low but still 10 times that of Clerks — Smith wrote and directed Chasing Amy.

By 1997 I was fully indoctrinated into the Cult of Kevin — as rabid a fanboy as any he’s had. I participated in his online message boards and I watched his first two films regularly (and convinced myself Mallrats wasn’t that bad… it is). Whatever Smith made next I would see. Yet the plot of Chasing Amy I found particularly interesting.

Alyssa (Adams) literally comes between Holden and Banky in this scene.

The film centers around two young independent comic book creators, Holden McNeil (Affleck) and Banky Edwards (Mallrats’ Jason Lee). The best friends find their relationship strained when Holden begins a romance with lesbian comic creator Alyssa Jones (Joey Lauren Adams; Smith’s then-girlfriend), spurring jealousy in Banky.

To me, the film seemed to be jumping on the bandwagon of “queer cinema” which had started to gain steam in the mid 90s. While mainstream Hollywood acknowledged gay characters in movies like Philadelphia and The Birdcage, it was really indie films that brought them to the fore, with such groundbreaking fare as My Own Private Idaho, The Crying Game, and Kiss Me, Guido.

Specifically, I saw in Chasing Amy echoes of Guinevere Turner’s Go Fish — a film Smith acknowledges as inspiration. Sexual preference felt like an exciting new frontier for films to tackle and, having seen all the ones I just mentioned, I likely would have seen Amy even with a complete unknown behind the camera.

I was actually a bit nervous to see Smith tackling LGBT topics. This was a straight man with a penchant for raunchy humor. In Clerks, for example, lead character Dante slut-shamed and dumped his girlfriend after finding out her sexual history. I wondered if Smith would use Alyssa’s sexuality as a source of humor, or to titillate his built-in male audience.

I was happily wrong. Chasing Amy is an exquisite balance of comedy and drama. The start of the film is right in line with Clerks’ humor, as militant black comic creator Hooper X (Dwight Ewell) dissects the racist undertones of the Star Wars trilogy. It was great fun, like a geeky twist on Tarantino’s Like a Virgin deconstruction in Reservoir Dogs. But the humor is nuanced. It’s quickly revealed that not only is Hooper’s rage an act to sell his comics, but he is also a closeted gay male and close friend of Banky and Holden.

As Holden and Banky, Affleck and Lee created a genuine on-screen friendship. It was one my friends and I related to…until the final twist.

The latter two characters would be familiar to Smith, and not just because both Affleck and Lee appeared in Mallrats. In Clerks, Mallrats, and again here, Smith features the same central duo: immature twenty-something white males with potty mouths. The primary character is more serious, contemplative, semi-neurotic, and dealing with relationship issues. The sidekick is wacky, always given the movie’s funniest lines, but given short shrift in the plot. Here, Holden was our Dante/Quint, and Banky was our Randall/Brodie. The jokes were raunchy and familiar, and the laughs hit hard.

More, Smith seems to know his audience. Any homophobes in the theater get their say through Lee, who spouts gay slurs and stereotypes throughout the film. Featuring gay characters in a positive light, and having Banky spout ignorance, was a subtle way of Smith attempting to educate a more narrow-minded contingent of fans.

Chasing Amy slowly changes tone, though. While all of Smith’s films had dealt with romantic relationships, none had been a romance film. Amy becomes that as Holden befriends unobtainable Alyssa. Their friendship is tinged with longing, and not just on Holden’s side — Alyssa’s feelings for a man make her question her own sexual identity. The scene where Holden confesses his feelings, followed by a rain-soaked argument, is moving and engrossing. There is barely a laugh to be had, and shows a maturity not before seen in a Kevin Smith film.

The film takes continued twists and turns, and jokes keep coming, but Smith had sharpened his humor into a blade, using it to cut the tension of many tense, dramatic scenes. The audience, engrossed in this tumultuous relationship full of self-doubt, would find their laughter a welcome release — the film allowing us to breathe again.

This kiss in the rain was Alyssa finally giving into her feelings for Holden. In most films that would be the end, but here it’s only the beginning of a journey full of self-doubt and jealousy.

While the romantic comedy fan in me was enjoying the Holden/Alyssa relationship, I was also empathizing greatly with Lee’s Banky. I was in my mid-20s and I had lost many friends to their girlfriends. I was all-too-familiar with the pattern of friends who hang out when they’re single, and then don’t return your calls when in a relationship. I saw Banky losing his lifelong friend to a new relationship, and, for the first time ever in a Smith film, I felt bad for the sidekick. Smith had finally created a supporting character with his own arc.

Holden and Alyssa’s relationship eventually hits the rocks when Holden finds out Alyssa was not always gay. The climax (so to speak) comes when Holden, desperate to save his friendship and his relationship, proposes a three-way to both Alyssa and Banky.

That was where the film took things too far. Until that point I felt Smith’s film had portrayed characters acting in ways that felt honest. This twist seemed to be the writer/director choosing to go with a wacky ending over a heartfelt one, or maybe he just wrote himself into a corner and couldn’t find a more earnest resolution.

The group sex idea felt totally outside the realm of Holden’s character. More, that Banky agreed, seemed to me a full character betrayal. I had completely understood Banky’s disappointment with a friend ditching him for a new relationship — it’s a real, common occurrence among single male friends. That Smith chose to write that entire emotion as based in latent homosexuality felt like a missed opportunity — an honest look at friendship was undermined by turning one character into a stereotypical gay male predator.

The film does recover from that moment, with an ambiguous ending that reminded me of The Graduate. Despite my disappointment with the final twist, the movie overall remained an on-screen romance that came across as honest and real. I left the theater entertained and believing Smith would be the next great voice of cinema.

He tried. His follow-up film, Dogma, attempted to analyze religion the way Amy deconstructed relationships, but to lesser effect. While amusing, the picture is scattered and scatological.

But it was with his next effort, Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, that I realized Smith was not an auteur with things to say, but a writer of increasingly insipid comedy. I first saw Smith speak at a convention in 2001, followed by a preview screening of Strike Back, and I realized he was a more amusing speaker than filmmaker.

History would prove that assumption true, as Smith is now an accomplished podcaster, while the best thing I can say about his post-Strike Back films is that there aren’t many of them.

I have seen all of Smith’s directorial efforts, always hoping to see even a hint of the filmmaker that made Chasing Amy. But from Jersey Girl to Zack and Miri Make a Porno to Cop Out and even Red State, Smith has become a serviceable, but completely unexceptional, director of (mostly unfunny) comedies. I would characterize Smith’s later directing work as on par with Tom Shadyac or Steve Carr. If you don’t know those names, you can look them up, but had Smith not been an indie darling in the mid 90s I don’t think you’d know his name either.

I don’t mean that to say Smith is a one-film-wonder, still coasting on Clerks, because I have gone back and watched his directorial debut — it doesn’t hold up. Jokes that pushed the envelope in 1994 now seem almost tame. More, Clerks is less a film than it is a series of sketches loosely tied together. I loved it when I was the characters’ age and related to their Generation X angst, but it is a movie with limited appeal that is quickly outgrown.

I had hoped that after Cop Out’s critical drubbing Smith might — as he did after Mallrats’ failure — return to his roots and make more personal films. That hasn’t happened. While he has done more low-budget films, such as Red State, it appears the filmmaker who made Chasing Amy is gone forever.

It is a shame. With Chasing Amy Smith showed himself to be a talented writer who could balance both comedy and drama with equal measure. It remains a go-to film when I want to laugh, one of the most honest romances caught on screen, and a progressive view of LGBT characters in cinema. Yet it’s the only Kevin Smith film I can recommend.

Tomorrow — 1998!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 27, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1990s, 40-Year-Old Critic, Ben Affleck, Chasing Amy, Comedy, Comic Books, Comics, Drama, Enertainment, Film, GLBT, Jason Lee, Kevin Smith, Lesbian, Movie, Movies, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Romance, Romcom | 2 Comments

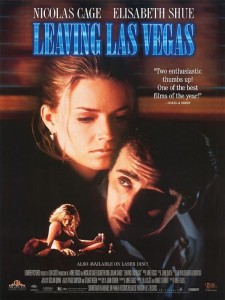

40 Year-Old-Critic: Leaving Las Vegas (1995)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

Have you ever had the feeling that the world’s gone and left you behind….

More than any other form of art, films have a soul. Moviegoers can experience a picture on more than an intellectual level; sometimes there is a base, emotional connection. Watching a great film can be akin to falling in love.

This is a view I first articulated while reviewing Gus Van Sant’s 1998 remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho for Now Playing Podcast (part of our Fall 2012 donation drive, that review is no longer available). That film showed two talented directors could take the same script, sometimes even the same camera shots, and produce different results. One filmmaker created art that engrossed and thrilled audiences, while the other produced a rote, mechanical and generic film.

Tens, hundreds, or even thousands of people — depending on the scope of the production — come together to create a single experience for a viewer. Even I sometimes forget this; the auteur theory takes hold and I focus on the director as sole creator of a vision. While the director usually maintains creative control, sometimes even through the editing stages, the movie itself is the result of millions of little decisions made by every actor, set dresser, composer, editor, and cameraman on the production. With the right people involved even the most mundane script can become a memorable experience.

One prime example of such a script elevated by those working on it is Leaving Las Vegas, the 1995 drama directed by Mike Figgis, starring Nicolas Cage and Elisabeth Shue. On paper, this movie seemed like the most trite of stories — depressed drunk Ben Sanderson (Cage) is a Hollywood screenwriter whose penchant for drink has ruined his every personal and professional relationship. When he is finally fired from his job he is ready to die, so he takes the last of his cash to Las Vegas where Ben plans to drink himself literally to death. In Vegas Ben hires a prostitute Sera (Shue), the damaged hooker with a heart of gold. The two lost souls fall in love, yet neither is willing or able to change their self-destructive habits.

These character tropes are so hackneyed that I would expect this to be a film made in the 1930s, when stories and characters were broader, and not the 1990s.

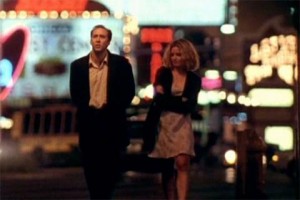

Cage in one of his more charming scenes, back-lit by the lights of the Vegas strip.

The film is based on a novel by John O’Brien. I have not read that book, but I have no doubt of O’Brien’s commitment to the material. Two weeks after discovering Leaving Las Vegas was to become a film, O’Brien used his gun to commit suicide. Clearly this was a man who understood the struggle with depression and the impulse to kill yourself. Yet, despite the insight his prose may offer, I have no interest in reading a book about two stereotypical characters going through a depressing endeavor. It may be very well written and I may be missing out, but the story itself sounds uninteresting.

Yet, despite cliched characters and a tired plot, in the hands of these filmmakers the result is a dramatically moving experience. Few movies I’ve seen in my life parallel the emotions stirred in me by Leaving Las Vegas, for what this team did, through filming and editing, was craft a film where the plot matters less and the characters matter more.

The tale is about a drunk, and the editing and filming often give the film a fugue-like ambiance. Sometimes the dialogue is crystal-clear, loud and in full focus. Other times the music mix raises. Sometimes you hear nothing as the actors’ lips move, other times there are words but you cannot make them out. It’s a dream-like experience that reminds me of techniques used by David Lynch.

The impact of the music cannot be overstated. The score, composed by Figgis himself, sounds like music played around 2 a.m. at an upscale bar. Heavy with piano and saxaphone, the music has a slow jazz feel that underlines the emotions of the moment. More, in an unusual move, some of the score is lyricized and sung by Sting. It blurs the line between soundtrack and score, but in the process creates sorrowful ballads of love and loss. Those original compositions intermix with covers of classic songs, such as “Lonely Teardrops” sung by Michael McDonald.

The sounds of the street often drown out character dialogue, to great effect.

The result sometimes feels like a depressing music video or an “in memoriam” montage, played while the characters still live. That Figgis is so willing to part with dialogue and just convey mood shows that in Las Vegas plot doesn’t matter. This is a character-driven story and we don’t need to hear their words to feel their pain.

This type of disregard for traditional narrative is used at the micro and macro scale. Sometimes the film cuts to the future suddenly, and we return to the present when Ben comes out of his stupor. We learn about the missing moments when Ben asks what happened. This is a movie told primarily from Ben’s shaky, out-of-focus point of view, and the camerawork and editing embody that mindset.

More than the cinematography, this film hops in and out of Ben’s own head. Sometimes we see Cage saying outrageous things, but then we discover it was only a fantasy in the character’s mind. In contrast, sometimes Ben makes equally offensive statements out loud and faces the very real consequence. As his blood alcohol content rises Ben cannot distinguish reality from fantasy, and, like Ben, the audience never knows exactly what is happening and what we can believe.

Of course, Figgis could not accomplish this alone. In the hands of a lesser actor than Cage Leaving Las Vegas could become an unintentional comedy quickly forgotten. Now, 20 years later, Cage is often disregarded, written off due to a long string of bad movies in which the actor makes unfortunate character choices.

Cage is an actor who gets off on playing characters in unconventional ways and giving them strange mannerisms. Often that will alienate the audience, but in Leaving Las Vegas Cage commits totally to the role. His body language exudes desperation. In one of the movie’s first scenes Ben is unintentionally sober, craving drink, and hitting up some colleagues for cash. He comes off sweaty, clumsy, and off-putting. One scene later, after a few drinks, Ben has an undeserved, over-inflated sense of self-confidence and makes improper advances on an attractive woman at the bar. It’s a wild swing of character, and is played perfectly through Cage’s intonation, eye work, and mannerisms.

This type of character could alienate audiences. Had viewers seen Ben as more creepy than sympathetic the result could be quite different. It’s little moments Cage plays, such as sobbing “I’m sorry” when being fired, that show humanity in this sad soul. It makes him someone we feel for, rather than pity.

I was a fan of Cage’s coming into Leaving Las Vegas, with Guarding Tess, Trapped in Paradise and Wild at Heart as highlights (though I’d also suffered through Kiss of Death, It Could Happen to You, and Amos & Andrew). Cage often gave captivating performances, but none I’ve seen before or since match his Oscar-winning performance here.

Despite how they meet, the relationship between Ben and Sera is about love, not sex.

Matching Cage’s portrayal is co-star Shue. In her roles in Back to the Future 2, Adventures in Babysitting, and even Cocktail I’d found the actress to be capable, but unexceptional. As Sera, Shue shows a range I’d never seen before. Early in the film Sera is a hooker, and very good at her job — she instinctively knows what the John wants, and becomes it. With Ben we see Sera start to open up. She lets down her guard, takes off her make-up, and becomes a real person. The transformation is startling, as is Shue’s lack of vanity in several unflattering scenes.

But Sera is not your normal streetwalker — she also has regular visits to a therapist. In these scenes we get to see inside Sera’s thoughts through monologues, confessions taken from her therapy session. As edited, these moments play like scenes from the confessional booth in MTV’s The Real World, but without them we would never be able to trust Sera. We never see the therapist; Shue is giving brief one-woman performances, but conveying pure emotion. This is a challenge for any actor, and she pulls it off. Shue fully deserved her Academy Award nomination for this performance.

Together Cage and Shue create a wholly believable, wholly dysfunctional, couple. Both broken characters are instantly drawn to the other. Though Sera knows Ben may be trouble, she puts that aside and chooses to follow her heart. The film avoids making their relationship too gross or base by actually, and believably, removing sex from the equation–while Ben hired Sera for physical gratification the liquor prevented him from performing. He becomes the only character not sleeping with Sera, even choosing to sleep on the sofa at night despite Sera’s repeated offers of more.

These two share a chemistry and a spark on screen that few romantic films can match. Though it’s a futile hope, it’s easy to root for these two to overcome their hardships through their new-found love.

Those two actors are the primary cast but even the minor roles are perfectly played by actors you’ll recognize; from Steven Weber (Wings, Stephen King’s The Shining), to comedian Richard Lewis, to Laurie Metcalf (Scream 2, Roseanne). It could almost be a drinking game — take a shot when you see an actor you know. With French Stewart, Shawnee Smith, R. Lee Ermey, Mariska Hargitay, and even, in the thankless role of bank teller, License to Kill’s Carey Lowell, you would be as drunk as Ben when credits roll.

No one on screen breaks the mood. Figgis has created his own Vegas, sometimes romanticized, sometimes demonized, but always real.

Leaving Las Vegas is a film with layers. On the surface, taken literally, the plot is about a terminal man and the woman who loves him as he dies. In such a bland interpretation, Sera is nothing but a fantasy, a female who serves a man’s needs. Sera describes herself as being instinctively able to become what her clients want, and she does that for Ben. Early in the film the drunk fantasizes of a woman pouring liquor on herself so he can drink off her, and she would have purpose. Ben never tells that to Sera, but she does that for him — alcohol and sex, Ben’s fantasy realized. Ben calls Sera, “my Angel”, and you could see her as nothing but.

Leaving Las Vegas is a film with layers. On the surface, taken literally, the plot is about a terminal man and the woman who loves him as he dies. In such a bland interpretation, Sera is nothing but a fantasy, a female who serves a man’s needs. Sera describes herself as being instinctively able to become what her clients want, and she does that for Ben. Early in the film the drunk fantasizes of a woman pouring liquor on herself so he can drink off her, and she would have purpose. Ben never tells that to Sera, but she does that for him — alcohol and sex, Ben’s fantasy realized. Ben calls Sera, “my Angel”, and you could see her as nothing but.

Yet to take that interpretation is to miss several important details. Sera is, in many ways, a mirror of Ben. Both came to Vegas from Los Angeles. Both are recently unemployed (Sera finding herself without purpose when Yuri, her lover and pimp played by Julian Sands, is murdered by Russian mobsters). Both characters are deeply wounded and on dangerous paths. And both accept each other unconditionally; Ben’s condition of being with Sera is that she never ask him to stop drinking. Likewise, Ben is accepting of Sera’s profession, knowing that she will continue to hook while he lives with her.

Finally, Ben’s course is a straight one. He starts and ends the film a drunk and he never waivers from his path of self-destruction. It would be nihilistic if his story was the only one in the film. Yet through loving Ben, Sera softens. The relationship forces Sera to mature, and she evolves from accepting her doomed relationship to trying to fix it, finally asking Ben to see a doctor. When Ben responds by bringing another woman home to her bed, she instantly kicks him out — she was not that strong when the movie began and she was working for Yuri.

Finally, Ben’s course is a straight one. He starts and ends the film a drunk and he never waivers from his path of self-destruction. It would be nihilistic if his story was the only one in the film. Yet through loving Ben, Sera softens. The relationship forces Sera to mature, and she evolves from accepting her doomed relationship to trying to fix it, finally asking Ben to see a doctor. When Ben responds by bringing another woman home to her bed, she instantly kicks him out — she was not that strong when the movie began and she was working for Yuri.

The star of the movie is clearly Cage as Ben, but every time I watch this film I become more convinced the true main character is Shue’s Sera. And it is through Sera that I found my own redemption in 1996.

That summer I had graduated college. My Communications degree and B-average in were not opening any doors. I had a small apartment in a boring town. Most of my friends had left for bigger cities and greater opportunities. My full-time job was working nights as tech support for an Internet company. It didn’t demand much; I sat alone in an abandoned building for eight hours a day, answering the phone on the rare occasion that it rang. It also didn’t pay much; I was living on $8.25 per hour.

Not that I had career aspirations. In college I spent my time doing my coursework and never got to the other things I wanted to do — write some screenplays or even publish some short stories. I had nothing to build my resume, and no idea what career path I should take. I still wanted to entertain people — that drive instilled since seeing Pump Up the Volume — but come fall, even my gig as a DJ would be taken away.

Despite having family living in my same town, we were never close. I preferred being alone in my dark apartment to spending time with them (and I loathed being alone). I was so desperate for friendly contact that, despite having graduated, I asked my college radio station if I could continue to work (for free) as a DJ through the summer.

Mostly, I was lonely. While friends would have alleviated this problem, to me the solution was a girlfriend. Many of my college friends had married soon after graduation. It is very easy for a lonely straight man to envision a woman as the answer to his troubles, and I certainly fell into that mindset. Yet with few friends, no social events to attend, and Internet dating not yet commonplace, I had no way to even meet a woman unless she happened to be delivering my pizza one Friday night.

With all these troubles, no money, few friends, bad job, no prospects, I was suffering from a deep depression.

I was never suicidal, but my overriding emotion was one of apathy, with a side of hopeless despair. My only pleasure in life came from movies. I couldn’t afford to see many in theaters, but I spent what little surplus income I had at the rental store week after week.

Ben’s constant fight against DTs show alcoholism isn’t a glamorous way to die.

That was when I found a kindred spirit in Ben Sanderson. Despite having recently turned 21, I was never much of a drinker. Still, there was something romantic in the very notion of going to Sin City and dying through copious consumption.

Yet through this act of destruction, Ben found his “angel” in Sera. And despite connecting with Ben’s depression, in Sera I saw strength and hope. Sera was in an equally bad situation — her “career” was short-term and dangerous. She was a smart, attractive woman, and even the Vegas cabbies were telling her she could do better than her station in life. When the movie ends Sera loses her love but gains hope for a brighter future.

Through Leaving Las Vegas’ trippy mood, moving characters, and tale of redemption I found my own. I was inspired out of my funk. Nothing happened quickly, but over the next four years my ambition redoubled, I went back to school to get a more employable degree, and I met my wife. But when my future seemed nearly as bleak as Ben’s, Leaving Las Vegas showed me the neon light at the end of a tunnel.

I believe that connection is partially because of the tragic, sad story presented, but the experience is heightened by Figgis’ choice to drop out dialogue and scenes. Figgis’ music created an emotional call-and-response; when the film’s dialogue was drowned out my own struggles filled in the blanks. When the dialogue faded out I would project my pain into the film, mixing with Ben and Sera’s until we were indivisible.

Even today, as I live a much happier, optimistic, and realized life, the film still moves me. You don’t have to be in pain to empathize with those in pain; you don’t have to hear their words to know their struggles.

This is where Leaving Las Vegas transcends being a movie and becomes a full, engrossing experience. This is the soul of a film.

Tomorrow — 1996!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 25, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1990s, 1995, 40-Year-Old Critic, Alcohol, Alcoholic, Drama, Elisabeth Shue, Enertainment, Film, Las Vegas, Leaving Las Vegas, Mike Figgis, Movie, Movies, Nicholas Cage, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Romance | 1 Comment

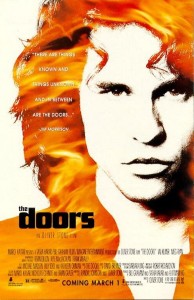

40 Year-Old-Critic: The Doors (1991)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

The critic awoke before dawn. He put his boots on. He chose a film from the ancient gallery and he walked on down the hall…

Believe it or not, I love the concept of film biographies, or biopics as they’re sometimes called. The world is full of colorful people with stories more strange and interesting than any fiction a Hollywood scribe can concoct. To learn a bit about a popular or historical figure, while also hopefully being entertained, seems like a win-win.

I realize this may be a shock to those who have heard my comments on the Now Playing Podcast review of The Aviator where I heaped my disdain on the overwrought, self-important Martin Scorsese-directed Howard Hughes biopic.

Therein lies the dichotomy: while I like the idea of a biopic, the execution is often lacking. A life cannot be compressed into a single film, so shortcuts are made to improve the narrative; and often the films come with this feeling that the director was saddled with the burden of making something to honor the subject.

Still, while they are the exception and not the rule, there are some biopics I completely love. Examples include: The Social Network’s profile of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, Fire in Silicon Valley (the TNT TV movie about the rise of Microsoft and Apple), and Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story, which feels like a martial arts film while profiling the star of that genre.

Of all of those, though, no biopic has had the impact on me that came with Oliver Stone’s The Doors.

It was by chance that I saw The Doors. My interest in a biography film is directly proportional to my interest in the subject. I don’t care about Peter Pan author J.M. Barrie, so I didn’t see Finding Neverland; I’m not a fan of Liberace so I didn’t seek out Behind the Candelabra.

From movement to posture to body shape, Kilmer became Morrison for The Doors.

In my teen years, not only wasn’t I a fan of The Doors, I barely knew them. I was more familiar with the Echo and the Bunnymen cover of People are Strange featured in The Lost Boys than I was any given Doors song.

Nor was I especially a fan of Stone’s (though this review series may give the opposite impression, as I already profiled Wall Street, and one more Stone film will appear before this series ends). After Wall Street I had seen Born on the Fourth of July and found it interesting, and I actually saw JFK before The Doors due to more interest in the subject. But JFK ended up becoming one of those biopics — like The Aviator — for which I have no tolerance.

I saw The Doors due to utter boredom. I was home from college for a weekend with no plans, so, as I was wont to do, I went to the video store with no agenda. A Saturday night, the new releases gone, I eventually came upon this film’s VHS box and saw Val Kilmer staring out at me, his hair and shirt aflame.

Kilmer was an actor I’d greatly enjoyed. Real Genius remains, to this day, one of my favorite 80s comedies, in large part due to the actor’s fun, yet emotional role as young laser scientist Chris Knight. In addition, Kilmer had given strong performances in Top Gun, Top Secret!, and Willow. I wanted to see what the actor could do if given a more serious role, and I had read nothing but praise for his portrayal of singer Jim Morrison.

I mostly knew co-star Kyle MacLachlan from Twin Peaks when I first saw The Doors. His character of Ray Manzarek, Doors’ keyboardist, is lost in this film; despite the title this movie is all about Morrison.

I took the videocassette home, with no clue what to expect. I knew nothing of Morrison’s life or his band. I certainly didn’t expect to see visions of Native American spirit guides, trippy sexual satanic rituals, and Morrison receiving oral sex in the recording studio while singing. While there were silent parts, it felt like Morrison’s life was completely scored to his own music — and it fit perfectly.

I had never done acid or eaten hallucinogenic mushrooms, but after watching The Doors I felt as if I had done both. Even on my small television I lost myself in this story. The editing, the score, the dreamlike quality that inhabits almost every frame, made me feel I had experienced the film, not watched it. The Doors took their name from Aldous Huxley’s book The Doors of Perception, and I felt mine had been opened through this biopic.

I ejected the tape feeling as if I had communed with Morrison, as he had on screen with the Native American.

Much of the credit for that must be given to Kilmer. Everything I had read, all the accolades heaped upon the actor, did not begin to do justice to this transformative performance. Despite watching the movie for him, by twenty minutes into the film I recognized that the actor had become lost to the role.

Part of it was a physical transformation — Kilmer losing weight to make himself as wiry as Morrison was in classic photos. More than just adjusting his body mass, though, Kilmer moved with a swagger I’ve not seen him have before or since. When he sang the songs he wasn’t just passable but exceptional. Somehow he captured the mystical authority that was Morrison’s trademark.

On my first watching of The Doors I didn’t realize how accurate Kilmer’s portrayal was; I knew nothing of Morrison and thus had no basis to which I could compare. What I did know, though, was that Kilmer had transcended the performances I had seen before and transformed into someone else for two-and-a-half hours.

Kilmer’s Morrison was sexy, cool, confident, cruel, drunk, stoned… he was magical. He was The Lizard King, he could do anything.

I had never desired to own a Doors record before this movie, but after delighting in this film I became obsessed. The very next day I went to the used music shop (where I was a regular) and bought some Doors CD’s that I listened to hundreds of times.

More, I wanted to find out the rest of Morrison’s story. The film showcased the high points but I needed to know more; about his supposed bastard child, about the satanic rituals he undertook, about his tumultuous relationship with girlfriend Pamela Courson (Meg Ryan, lost in Kilmer’s shadow). This being the pre-Internet era, I had to go to a bookstore, and within a week I had bought Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman’s biography No One Here Gets Out Alive.

This was not a short-term obsession. In the years since I’ve reread that book several times, as well as the autobiographies Riders on the Storm: My Life with Jim Morrison and The Doors by drummer John Densmore and Light My Fire: My Life with The Doors by keyboardist Ray Manzarek, and several other books along the way. I even bought a CD of a strange audio interview Morrison gave in his later years, and have listened to it religiously, looking for more insight into the man who hooked me on screen.

Kilmer perfectly recreates an iconic photo of Morrison.

Through those years of research I came to admire Stone’s work even more. It is impossible to sum up one man’s life in a single film, but Stone had come damn close. Though the surviving Doors disagree, my own readings show that Stone was mostly factual. With any real-life scenario there are different accounts of what happened, and even among the band there are disagreements about what in the film is fiction.

In the end, as with all biographies, some characters were combined or cut out, but it seems that Stone’s film did not indulge in the over-fictionalization and emotional shortcuts that are the hallmark of the genre. Even good biopics, like Dragon, rely on this crutch more than The Doors appears to have.

But beyond facts, Stone created a film that wasn’t about Jim Morrison, it was about being Jim Morrison. You didn’t need to see his every aspect so much as understand his point of view, and that is captured perfectly on film. Despite the seriousness of the subject, and contracts with Courson’s family and the remaining Doors, Stone kept the film light, fun, and trippy. He even avoided his JFK downfall — he never indulged a conspiracy theory over Morrison’s mysterious death in a bathtub. Several books propagate urban legend that Morrison’s death was faked, that Mr. Mojo Risin’ (an anagram of Morrison’s name) was living somewhere in Africa, and some day the world would witness the return of The Lizard King. That is subject material that seems tailor-made for Stone, but he does not follow the impulse. The result is a biopic that works as a movie, and a film that entertains as it educates.

Yes, while I only see most biopics due to an interest in the subject matter, this one was the total opposite — the biography film made me an uber-fan of the subject!

To this day The Doors is a film I watch regularly. It has stood the test of time better than its lead actor or its director. It has become iconic in my own mind, and when I envision Morrison in my head I’m never sure if I’m seeing Kilmer or Jim.

In the end, it doesn’t matter — for in this film they were one in the same.

Tomorrow — 1992!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 21, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Music, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 40-Year-Old Critic, Biography, Biopic, Documentary, Drama, Movie, Movies, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Oliver Stone, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Rock, The Doors, Val Kilmer | 4 Comments

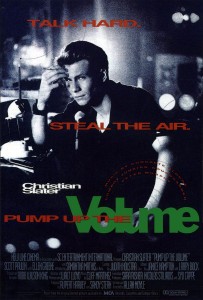

40 Year-Old-Critic: Pump Up The Volume (1990)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

Okay, down to business. I got my Wild Cherry Diet Pepsi, and I got my Blackjack gum here, and I got that feeling… mmmm… yeah, that familiar feeling, that it’s time to write another movie review.

I think every generation of teenagers has a movie that speaks to them directly. Maybe it’s Rebel Without a Cause or The Breakfast Club or Mean Girls or High School Confidential; there is always a movie that can perfectly capture on screen a snapshot of your fears and concerns, along with the overall attitude of American youth.

For many people my age — the younger members of Generation X — that film is 1990’s Pump Up the Volume, and it is in a large part the reason that I’m writing this entire review series.

The film stars Christian Slater as Mark Hunter, a high school student recently transplanted from New York to Arizona. At school he is an introverted kid who stumbles over his words and mumbles when called on in class. But by night Mark rocks out as Happy Harry Hard-On, a pirate radio DJ — his name stolen from the initials of the Hubert H. Humphrey High School he attends.

This looks like my studio. Only I have more toys, less records, and no reel-to-reel tape…but that would add atmosphere.

The show becomes a cult phenomenon at the school, with kids gathering nightly to listen in the remote locales that afford the best reception for Hard Harry’s low-powered FM transmission. Their communal experience stretches across class lines and cliques; and while Harry is simulating masturbation and playing banned Beastie Boys songs, he’s unaware that kids are looking up to him. As the audience grows Harry becomes an over-the-air Dear Abby for these pimple-popping pubescents. Unfortunately, one teen reaches out to Harry for help, and, when not satisfied with the response, commits suicide.

This leads to a contrived plot involving police and the FCC tracking down Mark on charges of criminal mischief. The film takes some Goonies-like kids-know-more-than-adults turns that stretch suspension of disbelief, and the last 30 minutes kind of fall flat as Mark tries to outsmart his pursuers. But the first hour truly succeeds in capturing the feeling of teen angst and insecurity shared by many high school students.

I know this film spoke to me in 1990. Like Mark, I had just moved to a new city, changing high schools in my junior year. That was my second move in three years, and I would live in five different cities over the span of four years. I always managed to make a small group of friends, but I understood Mark’s frustration. Also, like Mark, I avoided much of the situation by throwing myself into entertainment, be it books or films.

Each time I moved and lost contact with friends I’d have more free time to fill. Mark might as well have been speaking for me when he said, “I just arrived in this stupid suburb. I have no friends, no money, no car, no license. And even if I did have a license all I can do is drive out to some stupid mall, maybe if I’m lucky play some fucking video games, smoke a joint and get stupid. You see, there’s nothing to do anymore. Everything decent’s been done. All the great themes have been used up, turned into theme parks. So I don’t really find it exactly cheerful to be living in the middle of a totally exhausted decade where there’s nothing to look forward to and no one to look up to.”

Mark provided verbalization of my first post-modern early-life crisis.

My connection to this character was strengthened by Slater’s previous role as angsty, homicidal high school student J.D. in the dark comedy Heathers.

That film introduced me to the actor and his Jack Nicholson-esque delivery, and that’s why I was drawn to Pump Up the Volume. I have to say up front that Heathers is the better of the two films; both smarter and funnier.

In both films Slater’s character is an angry high school loner who seduces a brunette co-star while revealing the social hypocrisies that surround him. In many ways I saw Pump Up the Volume as a softer, less violent imitation of Heathers. I connected to Mark far more than J.D., the latter character’s mad bomber twist taking it a step too far.

As Mark, Slater took that angst and destroyed the school with words instead of dynamite. Through his one-man show he brought down a corrupt administration, got the girl, and made dozens of teens feel good about themselves.

It is the last point that gives Pump Up the Volume its power. Students call Harry’s hotline with problems so varied that everyone can find something to which they can relate. One pretty blonde girl is tired of pretending to be perfect. A gay teen is frustrated at the bullying he suffers. Another girl is kicked out of school after finding out she’s pregnant.

Gay or straight, male or female, fat or thin, Harry has self-affirming words of wisdom for you: “Feeling screwed up at a screwed up time in a screwed up place does not mean you are screwed up.”

All my listeners have this look of orgasmic rapture on their faces when listening to my podcasts, right? No??

Don’t destroy my fantasy!

In that way Harry becomes a horny radio version of Robin Williams’ John Keating from Dead Poets Society. He realizes that teenage years bring pain, but he’s wise enough to know it’s temporary and won’t matter in five years. (That Mark espoused this so convincingly while also lamenting his own station in life is a dichotomy the script never cares to rectify.)

Mark lives a Superman-like lifestyle. He is a geek by day, and even wears glasses to hide his identity. By night he takes the glasses off and is a microphone superhero. To the teens in his audience, and this teen watching the film, he was an inspiration.

I mentioned in my review of Wall Street that, after seeing that movie, I had no career ambition. Turning 16 years old but having no concept of career goals was frightening. Soon I would have to pick a college, a major, a career, and I had nothing. Yet Happy Harry Hard-On sparked something inside me. He made me realize the true power of words, and how few things are more insidious than a whisper in your ear; few things more important than entertainment that can lift your spirits after a terrible day. Pump Up the Volume made me want to be an entertainer, and, while I would experiment with several avenues, that goal of bringing light to peoples’ day never changed.

In fact, I took a fairly direct path from Pump Up the Volume. Three years after seeing this movie I became a DJ at my college radio station. I never found corruption in the school administration, but I did smoke my share of cigarettes while lamenting into a microphone and wondering if anyone was out there listening. I do know I remotely deejayed a number of parties on and off campus.

And I played more than my share of Leonard Cohen songs. I also must credit Pump Up the Volume for broadening my musical tastes. Cohen’s song “Everybody Knows” launched Harry’s every broadcast and its cynical lyrics resonated with me:

Everybody knows that the war is over

Everybody knows the good guys lost

Everybody knows the fight was fixed

The poor stay poor, the rich get rich

That’s how it goes

Everybody knows

Cohen’s sonorous voice sounded like a funeral march, and this became my anthem. I bought the Pump Up the Volume soundtrack immediately. Though I was disappointed that Cohen’s version of “Everybody Knows” was absent, replaced by Concrete Blonde’s cover, that CD introduced me to the Pixies and Henry Rollins, along with Soundgarden and Sonic Youth years before they broke into the mainstream.

I finally rediscovered Cohen a few years later, but that will be discussed in time.

I still live with Pump Up the Volume as an influence on my life, though as an adult I find few of the characters relatable; my own teenage angst and awkwardness are now, fortunately, long buried in the past. Yet, as I mention this film — which I long considered an obscurity — to people around my age I find we, like Harry’s on-screen audience, had a shared communal experience. Pump Up the Volume became a film that, despite its faults, resonated with us.

Rewatching this film to prepare for this review I found myself connecting with Hard Harry in a new way. When he finally tells the story of how he got started with his pirate radio, it was a familiar one. He started broadcasting thinking no one, or perhaps one special person, was listening. Slowly he realized his show was picking up steam. It was an incredible dream, and one I think nearly every podcaster shares.

Every podcast begins the same way: someone picks up a microphone and starts talking with no clue if anyone will listen. Some shows may have better odds than others, being featured on other podcast feeds and the like, but I know when I recorded my first episode of Star Wars Action News I wondered if anyone would ever hear it. That it got 50 downloads in the first week floored me, that was a number far greater than I’d ever dreamed. I continued to record, and people continued to listen. Like Harry experienced in this movie, my audience grew.

Podcasting is the new pirate radio, and we operate outside the purview of the FCC. And as Harry does at the end of the film I urge each of you to, “seize the air. Steal it! It belongs to you! Speak out! They can’t stop you. Find your voice and use it! Keep this going! Pick a name, go on air. It’s your life, take charge of it. Do it, try it, try anything. Spill your guts out, say shit and fuck a million times if you want to, but you decide. Just fill the air! Steal it! Keep the air alive!”

Until tomorrow’s entry, talk hard!

Tomorrow: 1991

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 20, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1990s, 40-Year-Old Critic, Christian Slater, Drama, Enertainment, Leonard Cohen, Movie, Movies, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Pump Up the Volume, Review, Reviews, Samantha Mathis | 1 Comment

Movie Review: The Place Beyond The Pines

The Place Beyond The Pines

Director: Derek Cianfrance

Writers: Derek Cianfrance, Ben Coccio, Darius Marder

Starring: Ryan Gosling, Bradley Cooper, Eva Mendes, Dane DeHaan, Emory Cohen, Ray Liotta

Studio: Hunting Lane Films

Release Date: March 29, 2013

The Place Beyond The Pines is a multigenerational saga like the Godfather. Characters will die. Others will rise to power. Some will fall from grace. However, unlike the Godfather saga, these characters are working class. Ordinary cops and bank robbers replace the glamorized mafia and FBI stings. Despite the lack of gangster fantasies, the film provides grounded, well developed characters that make for an emotional drama.

Luke (Gosling) quits his job as a stunt motorcyclist for a traveling carnival when he discovers he has a son in one of the towns his work brings him to annually. He turns to robbing banks when he is unable to find steady work to support his child. As he is pursued by police, a brief encounter with rookie cop Avery (Cooper) will change the course of Luke’s, Avery’s, and both of their sons’ lives.

Luke may seem threatening with his body covered in crude tattoos and his love for high speed motorcycling but Gosling is convincing that his character is kinder than he appears. There is a touching moment when Luke tells the mother of his child, Romina (Mendes), that he wants to be the first to feed their son ice cream to lessen the pain of being an absent father. The hurt and despair Luke feels for not being able to provide for his son is heartbreaking and lets the viewer sympathize with the character. When Luke turns violent and resorts to robbing banks to give his son a future, the tendency is to mourn rather than to harshly condemn his decision.

The film becomes a tense police drama as Avery’s path crosses with Luke in a high speed chase after Luke robs a bank. Cooper convinces us that Avery may have the book smarts to enforce justice, but not the street smarts to stay clean of corruption. The sleazy police workings are felt immediately as Liotta, playing corrupt cop Deluca, is introduced. His reassuring words and smile only heighten his threatening presence.

The movie loses some focus as it turns to examine the sons of Avery and Luke. Their fathers are more interesting, complex characters. These sons are forced into a rote tale of peer pressure. Two-thirds of the film I was engaged in examining characters that were well rounded and storytelling filled with emotion and tension. The third act is underwhelming as tough questions stop being asked and the film becomes an after school special.

Like the Godfather trilogy, The Place Beyond The Pines is hampered by a weak final third. The first two acts are filled with sorrow and tension that grip the viewer. The story may be multigenerational, but the children are never allowed to mature like the adult characters that held the viewer’s attention for most of the running time; making this film a mild recommend.

May 3, 2013 Posted by jakob | Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | dirt bikes, Drama, ryan gosling's abs | Comments Off on Movie Review: The Place Beyond The Pines

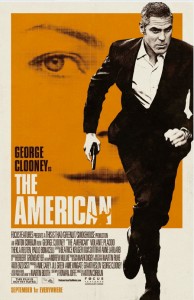

The American Movie Review

The American

Director: Anton Corbijn

Writer: Rowan Joffé

Starring: George Clooney, Violante Placido, Thekla Reuten, Paolo Bonacelli, Irina Björklund

Studio: Focus Features

Release Date: September 1, 2010

The American is a taut thriller. Every actor delivers an authentic performance that makes their character feel real. Every shot in the film is gorgeous and feels like each frame could be a postcard. The American may just be the best film I cannot possibly recommend.

Clooney plays Jack, a gunsmith and hit man on the run from relentless Swede assassins. In most movies with this type of set-up we would see Jack investigate his attackers, eventually uncovering their boss in an action-filled climax, but The American provides a refreshing, seemingly more realistic take. Instead of going on the offensive, Jack goes into hiding in the Rome countryside, counting on his employer Pavel to keep him safe. More, this attack has frightened Jack, making him want out of his lethal lifestyle.

It’s a very low-key, suspenseful take on a story about hit-men, and that is The American’s greatest strength. Even when Jack’s serenity is interrupted by a Swede attack, the action scenes are bloody and short, the exact opposite of the glossy, adrenaline-filled fights in action films like The Bourne Identity. The scenes are not here to thrill, but to remind Jack, and the audience, that death surrounds him and his quiet respite could come to a bloody end at any moment. This is driven home to great effect.

Indeed, The American treats the Swedes as a subplot, with the main focus being Jack’s relationship with local prostitute Clara. What starts as a purely professional relationship ends in a true romance as Jack connects with Clara, despite not ever truly trusting her intentions. Clara could be a plant, and we’ve already seen Jack kill one girlfriend. As such, Jack and Clara’s scenes together are always bittersweet as the audience knows at any moment one of these lovers could kill the other.

But despite all that is done right, The American fails in many respects. Jack is a laconic cipher We have endless scenes with him drinking coffee, or expertly machining a rifle, but Cloony’s performance always leaves us disconnected from the assassin. Jack’s lies are told so often and so easily that we never know what to believe. We don’t trust Jack and Jack trusts no one, leaving the viewer with no character with whom they can relate. Do we want this agent of death to find love and salvation, or do we want the Swedes to deliver swift justice?

The film’s final fall is in its finale. As we are kept emotionally distant from our main character, his fate becomes ultimately unimportant. The suspense of the eventual double-cross reaches its climax, but in an unfulfilling, perfunctory way.

The American is like one of Jack’s guns–lovingly crafted, expertly made, but ultimately cold and mechanical. Not recommend

March 19, 2013 Posted by Arnie C | Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | Assassin, Drama, George Clooney, independent film, Indie Film, Now Playing, Review, Suspense, Thriller | Comments Off on The American Movie Review

-

Archives

- February 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- November 2020 (3)

- October 2020 (2)

- September 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (2)

- July 2020 (1)

- June 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (3)

- March 2020 (2)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

Site info

Venganza Media GazetteTheme: Andreas04 by Andreas Viklund. Get a free blog at WordPress.com.