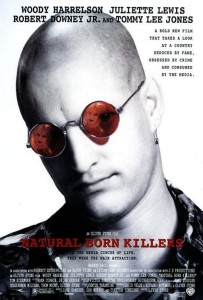

40 Year-Old-Critic: Natural Born Killers (1994)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

Mister rabbit says, “A movie review is worth a thousand prayers.”

In 1994 I was in college with aspirations of filmmaking. While my university did not have a dedicated film curriculum, my Mass Media Communications major with a Creative Writing minor afforded me classes in screenwriting, film criticism, editing, camerawork, and more.

But as the major was not simply film, there were numerous other classes I had to take for my degree. The list included Communication Ethics, First Amendment rights, studies of media impacts on the audience, and journalism, to name a few. As a college junior, I lived and breathed my major. Every form of entertainment I enjoyed, from video games to television to books to film, was a subject for my college studies. I wrote papers and gave multimedia presentations on violence in film, with a special focus on the Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street franchises.

But that year produced something unexpected from Oliver Stone and Quentin Tarantino. I was used to films factoring into my curriculum, but I never expected a major motion picture to be studying the same topic.

Natural Born Killers did just that.

The story is pure Tarantino. Having rewatched both True Romance and Reservoir Dogs multiple times I instantly saw a familiar trope in Mickey and Mallory Knox — the killers/anti-heroes of this film. Seeing two young outlaws in love and on a crime spree seemed right out of True Romance. That they are also merciless murderers felt like an extension of some of the characters from Reservoir Dogs — Mickey and Mallory could be Mr. and Mrs. Blonde. Finally, the film has a non-linear narrative that ends in a Mexican standoff. Despite Tarantino distancing himself from the production I saw his fingerprint on the negative.

Despite the carnage, there was something pure and romantic about Mickey and Mallory’s love affair. It was sick and twisted, but also sweet.

I did later read the original script, which was published in book form. That draft was far more Tarantino, but still a reach for the director. More than a crime film, Tarantino’s Natural Born Killers had a pointed critique on American tabloid journalism.

Yet, in the hands of Oliver Stone, the film’s focus on the media grew exponentially. Stone, along with screenwriters David Veloz and Richard Rutowski, rewrote the script to the point that Tarantino ended up only receiving story credit. In the hands of Stone’s team, Natural Born Killers became a scathing commentary on American media.

It could not have hit at a more appropriate time. Rush Limbaugh was scoring big on radioand television with his daily indictment of the Clinton administration. Meanwhile the country was transfixed by the O.J. Simpson case. While this movie was released a few months before the trial began, the Ford Bronco chase and Simpson’s arrest were constant news.

The media focus seemed to go from one real-life drama to the next, be it Amy Fisher, Tonya Harding, Heidi Fleiss, the Menendez brothers, or even Woody Allen’s divorce from Mia Farrow — all were fodder for the newspapers and 24-hour news channels. What had once been the domain of the National Enquirer was suddenly considered “real news.” It seemed everyone was being given a talk show, and those who couldn’t host a show tried to get their 15 minutes of fame by appearing on one.

It’s ironic that Stone undertook this film as a chance to make a simple action picture, but he doesn’t do “simple.” As such, the result is an indictment not only of the media companies that propagate such coverage, but also the populace that consumes it.

Mickey and Mallory Knox, as brought to life by Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis, are products of the media. Despite Harrelson being in his early 30s when this film was made, Mickey and Mallory feel like members of the “MTV Generation.” These two realize they will never be TV stars, so they’ll be the next best thing: headline-makers. They guarantee it, always leaving one person alive to tell the media about Mickey and Mallory.

Stone has never been accused of being too subtle.

The journalists are not left untouched, though. The second half of the movie gets a shot of adrenaline in the form of Robert Downey, Jr., turning in a tremendous performance as tabloid TV reporter Wayne Gale. With an affected Aussie accent and an equally affected sympathetic persona, Gale convinces Mickey to do his first TV interview. As the film’s madness grows Gale starts to believe his own press, and eventually realizes the time comes when the audience wants to turn the TV off.

From the first frame to the last, Natural Born Killers is a film about the superficiality of personas, examining the concept of who a person is versus how he/she wants to be seen. While that difference is often greatest in the cases of public figures who must act a certain way in public but may be very different behind closed doors, the script shows that everyone has that secret face. The insight to that is Detective Jack Scagnetti (Tom Sizemore), who appears to be the heroic cop who brings down Mickey and Mallory. Yet the audience sees that he is a mirror image to Mickey. While Mickey kidnaps, rapes, and murders an innocent woman, Scagnetti hires, screws, and strangles a hooker.

Every character in the film is disgusting and immoral–save one Navajo Indian from whom Mickey and Mallory seek shelter. This character calls out blatantly that the two killers watch “too much TV.” While the mystical, magical medicine man is a blatant stereotype, he is the only character in the film who doesn’t deserve a bullet (but he gets one anyway). The police, the media, Mallory’s parents, even the random stranger Mallory seduces at a gas station, are all contemptible and repugnant.

In other words, they’re the product, creators, and consumers, of tabloid journalism.

Yet, for all of the high-minded idealism of the movie, Natural Born Killers avoids the usual “message movie” pitfall of heavy-handedness, which I discussed in my review of Philadelphia.

Stone’s filmmaking is too frenetic, too fast-paced, to ever linger. The film’s style changes with the scene; one moment we are seeing Mallory’s family portrayed as a sitcom, complete with laugh track, the next we have grainy black-and-white footage. There are even animated sequences inserted into the film that visualize the emotion of a scene. There is no way for the film to linger, there is too much going on.

Something as simple as projecting a slide on actors felt fresh among the ever-shifting styles in Natural Born Killers.

In that regard, the picture is a critique of its audience. Stone knew that moviegoers in the 1990s had short attention spans, so he created a film perfectly suited to the mindset of an ADD-addled channel-flipper. The story and characters remain the same, but the tone, even the film stock, continually change. Stone also inserts bits of real commercials, as if he holds the remote we’re watching him scan to see what else is on.

The result is a trippy, psychedelic movie that truly feels like a tonal companion piece to his 1991 film The Doors. Mickey and Mallory are also rock stars of the media, and they even seek guidance from the spiritual Native American.

Like that earlier Stone film, Natural Born Killers is an experience more than a narrative. The color pallette, the transition to animation, the first-person camera shots years before found footage films were en vogue, the result is less narrative and more emotional.

And like The Doors, Natural Born Killers is propelled by a strong soundtrack. While the former film was almost exclusively set to Jim Morrison’s music, it was limited by the subject matter. Natural Born Killers doesn’t have that limitation, and the styles of music represented are as scattered as the film techniques.

Stone collaborated with Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor to produce the soundtrack, and the result is a thumping, yet moody, symphony of discord. Music from Patsy Cline is interwoven with Patti Smith, Bob Dylan, L7, Dr. Dre, and much more — with a healthy dose of Leonard Cohen at the beginning and end.

Listening to the soundtrack is almost as involving an experience as watching the film. Reznor did not simply follow the Reservoir Dogs formula of putting film clips on the CD, he actually mixed it with the music, creating an aural cinematic experience.

(Though for those of us who are musical purists, it also ensured I bought many of the bands’ original albums to have versions of the songs without added effects and dialogue. It was this album that set me on the road to Leonard Cohen super-fandom.)

This entire tone could have been undercut by the lead actors, but Stone directed his cast expertly. All the leads, and key supporting characters, have left realism at the door. Exaggeration is the name of the game, so lines are screamed or drawled, movements emphasized, and facial expressions broad. Alone, that type of acting could undermine a film, but with the crazed visuals that accompany the scenes anything more natural would be lost.

The standout of the cast is Harrelson. Much like Tom Hanks with Philadelphia, I knew Harrelson from his comedies — not just Cheers, but Doc Hollywood, White Men Can’t Jump and even The Cowboy Way. I worried he could not pull off a performance as a homicidal maniac. More, as Harrelson was the son of a hit man who may have been involved in the John F. Kennedy assassination, it felt like stunt casting of the worst type.

Harrelson left behind his good-ol-boy persona and fully inhabited the homicidal persona of Mickey Knox.

I was again wrong as I watched Harrelson, head shaved, fall into the character. By the film’s climax — when he has to break the fourth wall and deliver the line “I’m just a natural born killer” — all thoughts of comedy were gone. He was just a bad-ass, homicidal, rock star.

His performance is clearly aided by those of his co-stars. Lewis, a quirky actress I first noticed with 1993’s Cape Fear, is perfectly cast as a psychotic who becomes empowered and emancipated by following Mickey’s murderous examples. Sizemore carries a sleazy menace that follows him to every frame. Even Tommy Lee Jones overacts to the heavens as the spiteful prison warden. The result is a cast in perfect harmony, complimenting each other and their movie.

When I saw this film in theaters opening weekend I was mesmerized. I walked out, my head full of new viewpoints that I could incorporate into my coursework. I went back the very next day to try and catch more of the film, and to again experience the weird acid trip it offered.

Natural Born Killers spoke to me at a time in my life where I was already receptive to its message. I walked in expecting a road movie featuring mass murderers. I left thinking about media, and my own role in its creation.

But like Stone’s earlier film Wall Street, I feel the message of Natural Born Killers has been lost at best, or perverted at worst. Several instances of “copycat crimes” have appeared in the media, killers completely missing the point and, instead, are seemingly inspired by Mickey and Mallory Knox. It’s impossible to say if those acts would have been done without this film, but it’s a sad irony that a movie about the dangers of media violence then creates its own.

Yet every day when I look at the news, I feel that Natural Born Killers did not succeed in warning the media, or its consumers, about the impact of tabloid journalism. From Britney Spears’ head-shaving incident to Charlie Sheen’s “winning” display to even Robin Williams’ tragic suicide, the media is there to try and grab big ratings under the guise of informing the public.

On TV, audiences laughed at the obviously drugged antics of Anna Nicole Smith, until she died from her drugs. Audiences insist on Keeping Up with the Kardashians and watching Honey Boo Boo, The Bachelor or Catfish. Producers and editors sculpt clips from those shows, take sound bites out of context, and spend thousands of hours creating an audience-pleasing narrative of good versus bad that may have little bearing on reality.

I don’t know if fans of these shows a) don’t realize they manipulate the stars and their audience, or b) don’t care. Either way, we continue down the spiral to Stone’s original vision.

But if Natural Born Killers’ message didn’t last, the film didn’t stick with me either. Through my college years Stone’s film was in heavy rotation on my VCR. When the VHS release of the Director’s Cut came in 1997 (so long it had to be on two tapes) I rented it the first day. That was when I felt the trippy effect had finally worn off and I was no longer under the movie’s spell.

The scenes cut from Natural Born Killers — available on the second VHS tape — had every reason to be cut. I watched the extra hour Stone filmed for this movie and realized that, truly, this was a film made in the editing bay and not on the set. Assembling all the footage, including the cut trial scene and Mickey and Mallory’s attack on wrestling brothers Simon and Norman Hun, I realize Stone had a production out of control. The behind-the-scenes knowledge soiled this film for me, and for a decade I had trouble watching it at all. Now I can credit the final product, knowing how bad this movie almost was.

But in the fall of 1994 two Tarantino scripts were in theaters simultaneously: Natural Born Killers and Pulp Fiction. The masses crowded around Fiction, and Tarantino took home Oscar gold.

I greatly enjoy that second Tarantino-directed film, but if you asked me in the mid-90s to name my favorite of those two works, it had to be Natural Born Killers.

Tomorrow — 1995!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 24, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1990s, 40-Year-Old Critic, Juliette Lewis, Mallory, Mickey, Movie, Movies, Natural Born Killers, Nine Inch Nails, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Oliver Stone, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Robert Downey Jr, Trent Reznor, TV series, Woody Harrelson | 2 Comments

40 Year-Old-Critic: The Doors (1991)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

The critic awoke before dawn. He put his boots on. He chose a film from the ancient gallery and he walked on down the hall…

Believe it or not, I love the concept of film biographies, or biopics as they’re sometimes called. The world is full of colorful people with stories more strange and interesting than any fiction a Hollywood scribe can concoct. To learn a bit about a popular or historical figure, while also hopefully being entertained, seems like a win-win.

I realize this may be a shock to those who have heard my comments on the Now Playing Podcast review of The Aviator where I heaped my disdain on the overwrought, self-important Martin Scorsese-directed Howard Hughes biopic.

Therein lies the dichotomy: while I like the idea of a biopic, the execution is often lacking. A life cannot be compressed into a single film, so shortcuts are made to improve the narrative; and often the films come with this feeling that the director was saddled with the burden of making something to honor the subject.

Still, while they are the exception and not the rule, there are some biopics I completely love. Examples include: The Social Network’s profile of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, Fire in Silicon Valley (the TNT TV movie about the rise of Microsoft and Apple), and Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story, which feels like a martial arts film while profiling the star of that genre.

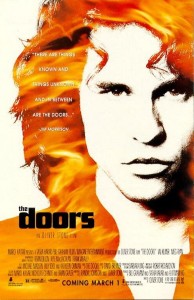

Of all of those, though, no biopic has had the impact on me that came with Oliver Stone’s The Doors.

It was by chance that I saw The Doors. My interest in a biography film is directly proportional to my interest in the subject. I don’t care about Peter Pan author J.M. Barrie, so I didn’t see Finding Neverland; I’m not a fan of Liberace so I didn’t seek out Behind the Candelabra.

From movement to posture to body shape, Kilmer became Morrison for The Doors.

In my teen years, not only wasn’t I a fan of The Doors, I barely knew them. I was more familiar with the Echo and the Bunnymen cover of People are Strange featured in The Lost Boys than I was any given Doors song.

Nor was I especially a fan of Stone’s (though this review series may give the opposite impression, as I already profiled Wall Street, and one more Stone film will appear before this series ends). After Wall Street I had seen Born on the Fourth of July and found it interesting, and I actually saw JFK before The Doors due to more interest in the subject. But JFK ended up becoming one of those biopics — like The Aviator — for which I have no tolerance.

I saw The Doors due to utter boredom. I was home from college for a weekend with no plans, so, as I was wont to do, I went to the video store with no agenda. A Saturday night, the new releases gone, I eventually came upon this film’s VHS box and saw Val Kilmer staring out at me, his hair and shirt aflame.

Kilmer was an actor I’d greatly enjoyed. Real Genius remains, to this day, one of my favorite 80s comedies, in large part due to the actor’s fun, yet emotional role as young laser scientist Chris Knight. In addition, Kilmer had given strong performances in Top Gun, Top Secret!, and Willow. I wanted to see what the actor could do if given a more serious role, and I had read nothing but praise for his portrayal of singer Jim Morrison.

I mostly knew co-star Kyle MacLachlan from Twin Peaks when I first saw The Doors. His character of Ray Manzarek, Doors’ keyboardist, is lost in this film; despite the title this movie is all about Morrison.

I took the videocassette home, with no clue what to expect. I knew nothing of Morrison’s life or his band. I certainly didn’t expect to see visions of Native American spirit guides, trippy sexual satanic rituals, and Morrison receiving oral sex in the recording studio while singing. While there were silent parts, it felt like Morrison’s life was completely scored to his own music — and it fit perfectly.

I had never done acid or eaten hallucinogenic mushrooms, but after watching The Doors I felt as if I had done both. Even on my small television I lost myself in this story. The editing, the score, the dreamlike quality that inhabits almost every frame, made me feel I had experienced the film, not watched it. The Doors took their name from Aldous Huxley’s book The Doors of Perception, and I felt mine had been opened through this biopic.

I ejected the tape feeling as if I had communed with Morrison, as he had on screen with the Native American.

Much of the credit for that must be given to Kilmer. Everything I had read, all the accolades heaped upon the actor, did not begin to do justice to this transformative performance. Despite watching the movie for him, by twenty minutes into the film I recognized that the actor had become lost to the role.

Part of it was a physical transformation — Kilmer losing weight to make himself as wiry as Morrison was in classic photos. More than just adjusting his body mass, though, Kilmer moved with a swagger I’ve not seen him have before or since. When he sang the songs he wasn’t just passable but exceptional. Somehow he captured the mystical authority that was Morrison’s trademark.

On my first watching of The Doors I didn’t realize how accurate Kilmer’s portrayal was; I knew nothing of Morrison and thus had no basis to which I could compare. What I did know, though, was that Kilmer had transcended the performances I had seen before and transformed into someone else for two-and-a-half hours.

Kilmer’s Morrison was sexy, cool, confident, cruel, drunk, stoned… he was magical. He was The Lizard King, he could do anything.

I had never desired to own a Doors record before this movie, but after delighting in this film I became obsessed. The very next day I went to the used music shop (where I was a regular) and bought some Doors CD’s that I listened to hundreds of times.

More, I wanted to find out the rest of Morrison’s story. The film showcased the high points but I needed to know more; about his supposed bastard child, about the satanic rituals he undertook, about his tumultuous relationship with girlfriend Pamela Courson (Meg Ryan, lost in Kilmer’s shadow). This being the pre-Internet era, I had to go to a bookstore, and within a week I had bought Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman’s biography No One Here Gets Out Alive.

This was not a short-term obsession. In the years since I’ve reread that book several times, as well as the autobiographies Riders on the Storm: My Life with Jim Morrison and The Doors by drummer John Densmore and Light My Fire: My Life with The Doors by keyboardist Ray Manzarek, and several other books along the way. I even bought a CD of a strange audio interview Morrison gave in his later years, and have listened to it religiously, looking for more insight into the man who hooked me on screen.

Kilmer perfectly recreates an iconic photo of Morrison.

Through those years of research I came to admire Stone’s work even more. It is impossible to sum up one man’s life in a single film, but Stone had come damn close. Though the surviving Doors disagree, my own readings show that Stone was mostly factual. With any real-life scenario there are different accounts of what happened, and even among the band there are disagreements about what in the film is fiction.

In the end, as with all biographies, some characters were combined or cut out, but it seems that Stone’s film did not indulge in the over-fictionalization and emotional shortcuts that are the hallmark of the genre. Even good biopics, like Dragon, rely on this crutch more than The Doors appears to have.

But beyond facts, Stone created a film that wasn’t about Jim Morrison, it was about being Jim Morrison. You didn’t need to see his every aspect so much as understand his point of view, and that is captured perfectly on film. Despite the seriousness of the subject, and contracts with Courson’s family and the remaining Doors, Stone kept the film light, fun, and trippy. He even avoided his JFK downfall — he never indulged a conspiracy theory over Morrison’s mysterious death in a bathtub. Several books propagate urban legend that Morrison’s death was faked, that Mr. Mojo Risin’ (an anagram of Morrison’s name) was living somewhere in Africa, and some day the world would witness the return of The Lizard King. That is subject material that seems tailor-made for Stone, but he does not follow the impulse. The result is a biopic that works as a movie, and a film that entertains as it educates.

Yes, while I only see most biopics due to an interest in the subject matter, this one was the total opposite — the biography film made me an uber-fan of the subject!

To this day The Doors is a film I watch regularly. It has stood the test of time better than its lead actor or its director. It has become iconic in my own mind, and when I envision Morrison in my head I’m never sure if I’m seeing Kilmer or Jim.

In the end, it doesn’t matter — for in this film they were one in the same.

Tomorrow — 1992!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 21, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Music, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 40-Year-Old Critic, Biography, Biopic, Documentary, Drama, Movie, Movies, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Oliver Stone, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Rock, The Doors, Val Kilmer | 4 Comments

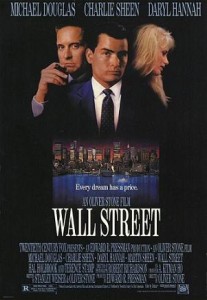

40 Year-Old-Critic: Wall Street (1987)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

Growing up I wanted to be a stockbroker. Other kids said they wanted to be astronauts, movie stars, or firemen; I said stockbroker. In my preteen years I upgraded that to investment banker.

Why wouldn’t I want to go into that world? I grew up in the big 80s, the era of Reaganomics. Money was being flashed everywhere, and it wasn’t just the musicians and actors who had rich and famous lifestyles; there were also names like Ivan Boesky, Carl Icahn, Jordan Belfort, and Donald Trump.

My godfather, who rode the stock market to a healthy retirement, told me that the brokers had the best gig — no matter if their clients won or lost, the broker got the commission.

What did I really want to be when I grew up? I wanted to be rich. I saw the stock market as the avenue to that lifestyle. When I turned 13 I even became a stock owner, my godfather buying me some shares of Ohio-Edison.

That dream crashed in 1987, starting with Black Monday, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 508 points (which would still make headlines today, but back then it was almost 25 percent of the Dow’s value). I heard stories of broker suicides and rich people in ruin. My faith in the avarice of the economy was shaken.

As a child this wasn’t how I envisioned the job of a stock broker.

It was broken entirely two months later when I saw Oliver Stone’s Wall Street. I had looked forward to that film for months. I didn’t know much about Stone (I hadn’t yet seen Platoon), but I knew his name and his Oscar-winning reputation.

Had I researched the man further I would have known that Wall Street wasn’t going to be what I expected, which was a more realistic version of The Secret of My Success.

Instead I saw a film to which I could relate a bit too well. Charlie Sheen played Bud Fox, an up-and-coming broker barely making ends meet. The early scenes that give you a glimpse into the life of the average, front-line broker did not depict the glamorous lifestyle I’d seen on television — it actually looked like Bud might have earned less than a talented bartender.

The high-pressure nature of the business and the cold-call sales techniques combined to make Bud hungry and bitter. Even as a kid I could relate to him; his drive to get out of the phone pool and make a name for himself.

But then we were introduced to Michael Douglas as Gordon Gekko. I had seen Douglas a few months earlier in Fatal Attraction and thought of him as a good guy. In Wall Street he’s a ruthless, wealthy businessman, but I envisioned him almost as a guardian angel that would show Bud the road to riches.

Instead Gekko turned out to be a greedy, deceitful, vengeful criminal. He corrupted Bud with promises of women and riches until the young businessman betrayed his own father in service of his mentor.

Bud redeemed himself — he came up with a plot to save his father’s company — and served time for his misdeeds, but as Sheen’s character was taken to prison I found myself finally questioning this lifestyle I had coveted for years.

Stone told the story exactly how it should have been told in 1987; show the flash, the cash, the allure of riches in the big 80s. Then show the cost, including the broken relationships, the drug hangovers, and the realization that Bud’s “friends” (and even his girlfriend) all disappeared when the money was gone.

This was the image that struck me hardest from the film. Not the penthouse, not the girl, but the consequences.

This was a movie with a social commentary, and one that should have been made louder and more often in the 80s. The “Greed is Good” mentality prevailed as the economy boomed, but while the success stories got the press, little attention was paid to the illegal and immoral activities undertaken by so many to achieve those ends.

More, the film could not have had a luckier release schedule, if you can ever call Black Monday “lucky.” The stock market was on everyone’s minds and tongues, questioning this ethereal concept of non-liquid assets in a grand trading scheme. Stone’s message rang true, for a period.

I now feel the message of Wall Street has been lost. The stock market is more vital to the lives of Americans than ever thanks to 401(k) plans and other reliances. Despite the crash of the NASDAQ at the turn of the century (when several of my close friends lost everything) and the crash of the Dow in 2007, it seems Americans still like to play the market like a Blackjack table.

More, Gordon Gekko and his “Greed is Good” speech have become lionized by today’s hungry, young businessmen. Even this year’s The Wolf of Wall Street seemed to play up the glamour of Jordan Belfort’s illegally-funded lifestyle rather than focus on the victims he snookered.

“Please allow me to introduce myself. I’m a man of wealth and taste.”

Had Stone been a different filmmaker and Wall Street a more Wolf-ish tale perhaps my ambitions would have redoubled. I might be a very wealthy man today, or I might be in prison. Fortunately I saw the right movie at the right time. In 1987 and now, Stone’s message rang true. I went in wanting it all, and I left the theater a boy without a goal, perhaps slightly more normal for that.

For that life-changing course — setting me on a path where I would end up helping people by day and entertaining people by night — Stone’s film will always remain a profound symbol of how art can change the direction of your life.

Not all films are pure entertainment, the best ones raise questions as well.

Tomorrow — 1988!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 17, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1980s, 1987, 40-Year-Old Critic, Bud Fox, Charlie Sheen, Enertainment, Film, Gordon Gekko, Michael Douglas, Movie, Movies, News, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Oliver Stone, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Stock Market, Wall Street | 2 Comments

-

Archives

- February 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- November 2020 (3)

- October 2020 (2)

- September 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (2)

- July 2020 (1)

- June 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (3)

- March 2020 (2)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

Site info

Venganza Media GazetteTheme: Andreas04 by Andreas Viklund. Get a free blog at WordPress.com.