The 40 Year-Old-Critic: Freddy vs. Jason (2003)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

How many times will I review Freddy vs. Jason? It was one of Now Playing Podcast’s earliest reviews as part of our first retrospective series covering the Friday the 13th franchise leading up to the 2009 remake. Even then we planned to revisit the film and look at it from Freddy’s point of view, which we did the following year during the review series leading up to 2010’s A Nightmare on Elm Street.

By now this should be well-trod ground, and what more could I have to say?

Yet the fact that this is the only movie to be covered twice in Now Playing Podcast retrospectives is indicative of its importance — to film in general and to me personally.

Since our 2010 review I’ve spent a lot more time thinking about the crossover. What is it about two franchises coming together that creates such excitement, especially in the “geek” community? I don’t ask this hypothetically. I personally get swept up in the frenzy when two franchises come together, and it doesn’t even matter necessarily if I like them both! The thought of two universes colliding seems to have a geometric, not additive, increase in interest.

I think to some degree it is fan rivalry at its best. For reasons I don’t understand it seems some fans feel the only way to feel good about their fandom is by putting down others. For example, when Firefly was at its zenith a parade of “Joss Whedon Is My Master Now” shirts filled Star Wars conventions, as if to say, “Star Wars used to be cool.” As such, the “my dad can beat up your dad” mentality started to apply to fan groups; “My stormtrooper can beat up your browncoat.”

Freddy vs. Jason — whoever loses, the fans win.

That question of who would win in a fight certainly applies to superheroes. In real life, on screen, and online I’ve heard endless debates about which hero is faster, The Flash or Superman. Who would win in a fight, Superman or The Hulk? It is a curiosity, but the chosen winner usually aligns with the speaker’s fan allegiances.

Certainly, speaking of superheroes, comic books have benefited greatly from the crossover. DC Comics had a major hit with its Justice League in 1961, prompting Marvel Comics to respond with its own super team, The Fantastic Four, a move that inadvertently launched the entire Marvel Universe.

Yet, to me, the crossover seemed relegated to just that medium — the comic book. It seemed comics were pulp enough that you could do anything.

Aliens vs. Predator? Sure.

Robocop vs. Terminator? Why not.

Star Trek and X-Men together, you say? Absolutely.

Even rivals Marvel and DC had several crossover series’ that, for instance, led to Superman meeting Spider-Man or Batman fighting the Hulk.

Despite the success and excitement generated by these crossover comics, the concept was rarely conceptualized on film. Universal Studios had done it in the 1940s, when horror icons Dracula, Frankenstein and the Wolf Man came together for the studio’s “Monster Mash” pictures. But Universal owned each property, and when that series ended, crossovers on screen were scarce.

I can recall two that made an impact on me.

Freddy and Jason aren’t the only names in this cast. Monica Keena (Dawson’s Creek), Katharine Isabelle (Ginger Snaps), and Destiny Child’s Kelly Rowland play teens caught in the middle of the battle royale.

I remember being a young child on vacation with my parents when I saw a trailer for King Kong vs. Godzilla. I had seen numerous Godzilla films, and the 1976 King Kong several times. So the thought of them fighting broke my fragile little mind. I demanded we stay in the hotel room that night so I could watch.

Then, in 1988, Who Framed Roger Rabbit brought together animated characters from Warner Bros., Disney, Turner Entertainment, and more. As I was a teenager, and never really into these characters at my youngest age, the impact was totally lost on me. I saw the film in theaters, thought it was mediocre, and haven’t seen it since.

Beyond those two I can’t think of any groundbreaking crossovers. Some minor ones occurred; such as Star Trek: Generations bringing together cast members from two Trek television series’ (something that had already been done numerous times on Star Trek: The Next Generation, thus lessening the film’s impact). Also, The Monster Squad reassembled the classic Universal Monsters for a kiddie comedy.

But fans wanted more.

So many ideas were teased. Studios knew what we liked, so 1997’s Batman and Robin made sly references to Superman, and 20th Century Fox put an Alien xenomorph skull on a Predator ship in Predator 2. The latter seemed most likely to happen again on film — both franchises were Fox properties in need of a boost. Yet, outside of the Dark Horse comics, nothing materialized for years.

For me, though, more than Aliens and Predators, more than Superman and Batman, Freddy and Jason were the two I wanted to see. Long had the rumor brewed about Hollywood’s (then) top-grossing slashers, Jason Voorhees and Freddy Krueger, going toe-to-toe. I read about it in multiple Fangoria articles in the late 80s and early 90s.

I first saw A Nightmare on Elm Street during a party in 1987, around the time of A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: The Dream Warriors’ release. I found the films so inventive and fun that I rewatched them endlessly, and anxiously awaited each new installment in the series. As detailed during the Now Playing Podcast review, I even cosplayed for the release of Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare. By 2003 I was happy for any new Nightmare, let alone one that pitted villain Freddy against Friday the 13th icon Jason.

I was never as big a fan of the Crystal Lake zombie as I was Freddy, but I did also enjoy the Friday the 13th series. Some of the first R-rated horror I ever saw was Friday the 13th when I came home to find older kids in my house watching it. I tried to join them but the carnage, specifically the decapitation at the end of the 1980 original film, had me fleeing the room. When I finally became a full-fledged horror hound in my early teen years I returned to the franchise when Jason Takes Manhattan was released. While the films lacked the visual panache of the Nightmare series I still enjoyed the films as a guilty pleasure. Over time the series grew in my esteem to be another favorite.

Freddy was killed by fire, but flames don’t slow down Jason.

As such, having both serialized slashers come together would be a dream come true. Or, if done wrong, perhaps a nightmare.

Yet despite the rumors in the horror press and the anticipation by fans such as myself, the killer crossover took 15 years to materialize. Full credit for finally bringing the crossover to screen in the 21st Century must be given to New Line Cinema.

The biggest problem in the 1980s and 1990s was the rights: Jason was owned by Paramount, Freddy was New Line Cinema’s cash cow. The studios tried to work together during the slasher heyday but each wanted to earn 100 percent of the profits by licensing the other’s character. Obviously, that never happened.

Eventually, though, profits started to dry up. Paramount had run Friday the 13th into the ground with crazy concepts like Jason fighting a telekinetic or taking Manhattan. When original Friday creator Sean S. Cunningham wanted to see the franchise continue, specifically with a Freddy crossover, Paramount had no interest. This gave New Line an opportunity. They licensed Jason from Paramount and went to work on Freddy vs. Jason.

While Jason’s creator wanted the crossover, Freddy creator Wes Craven had other ideas. The Springwood Slasher had been given what New Line considered a proper sendoff with 1991’s Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare. But the sequel proved profitable and Craven started planning a return to his iconic franchise. As such, Freddy vs. Jason was put on hold and, instead, Wes Craven’s New Nightmare was made.

Cunningham bided his time, though. In 1993 Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday was released and ended with a fan-baiting stinger; Freddy’s glove comes out of the ground and pulls down Jason’s mask. The game was afoot!

We would still have to wait more than a decade for Freddy and Jason to properly share the screen. New Line executives knew the importance of finding the perfect balance between the two famous killers, and so more than a dozen pitches were drafted and subsequently rejected.

More victims caught in the middle of the killer clash.

Eventually I gave up all hope on Freddy vs. Jason. Nightmare star Robert Englund had not put on the makeup in almost 10 years and I thought Freddy would never grace the screen again. Jason, meanwhile, had gone to space with Jason X (which sat on a shelf for 2 years before its release). Finally, in the early part of the last decade, news — real news — started to come out that the movie was being made.

I honestly believe my excitement for Freddy vs. Jason was on par with my feelings about 1999’s Star Wars Episode I. A countdown clock sat on my computer desktop for 4 months, and when the day finally came I took an afternoon off work to see the first showing.

It met my every expectation.

Directed by Bride of Chucky’s Ronny Yu, the film was outrageous, gory, and over-the-top fun. Both characters got their due (even if Jason inexplicably was suddenly afraid of water) and I couldn’t have asked for more. You can hear a blow-by-blow analysis and both of my reviews at the Now Playing Podcast website, but in short I gave it a strong recommend both times.

Yet loving a movie isn’t enough to garner inclusion in this 40-Year-Old Critic series, there has to be a long-lasting impact. For Freddy vs. Jason, there were two.

First, this film gave Robert Englund a proper Freddy sendoff. It was the best film starring the dream stalker since 1988’s The Dream Master. It cemented a positive feeling for the Nightmare franchise that remains unsullied to this day. Just two weeks ago I had my photo taken with Englund, who was dressed in the full Freddy make-up. I even have ideas for a Nightmare inspired tattoo–the dream killer’s glove slicing into my skin.

Freddy vs. Arnie — Robert Englund and Arnie pose for a photo at Flashback Weekends in Aug. 2014

Second, though, Freddy vs. Jason’s success launched more than a decade of franchise crossovers. The next year finally saw the release of Alien vs. Predator, which I anticipated every bit as much as Freddy vs. Jason — and which was an utter letdown.

Other pictures released that year include the low-rent, made-for-television crossover Puppet Master vs. Demonic Toys (co-written by Blade and The Dark Knight scribe David Goyer), as well as a return to the “Monster Mash” formula with Universal’s Van Helsing.

Yes, the track record for crossovers wasn’t stellar, but that was honestly my secondary concern — the primary concern was that they were happening. Finally, after decades of teasing, universes were being shared and the world of movies suddenly felt as open as the page of a comic book. But, after 2007’s Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem a shot of adrenaline was needed. I do think the crossover was starting to be seen as desperate, until Marvel Studios took it to the next level.

In 2008 Marvel released its first movie produced in-house: Iron Man. The film stood alone, introducing wide audiences to a superhero that was considered B-list at best. Yet Marvel took a page from New Line Cinema’s book: at the very end Nick Fury showed up to discuss “The Avengers Initiative.” This was the comic book equivalent of Freddy’s hand bursting up from the ground, and Marvel kept its momentum building toward the third-highest-grossing film of all time: The Avengers.

There is a direct lineage from Jason Goes to Hell to Iron Man, from Freddy vs. Jason to The Avengers.

So next spring when you buy your ticket for The Avengers: Age of Ultron (and then download the Now Playing Podcast review) think about the trailblazer that pioneered the modern crossover film: Freddy vs. Jason.

Tomorrow — 2004!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

September 2, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Comic Books, Conventions, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 40-Year-Old Critic, Avengers, Comic Books, Comics, Crossover, Enertainment, Film, Freddy, Friday the 13th, horror, Iron Man, Jason, Movie, Movies, Nightmare on Elm Street, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Ronnie Yu, Sean S. Cunningham, Slasher, Wes Craven | Comments Off on The 40 Year-Old-Critic: Freddy vs. Jason (2003)

The 40 Year-Old-Critic: Armageddon (1998)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

How Arnie Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Asteroid

I’ve often referenced Armageddon on Now Playing Podcast, and, shockingly, those comparisons are usually favorable. This has led to many a raised eyebrow and gentle mocking — even from co-hosts who have never seen Michael Bay’s 1998 blockbuster (you know who you are).

So, though 1998 contained many movies that influenced me, from Bride of Chucky to Pi to Your Friends and Neighbors to Very Bad Things, I think I must take the opportunity to discuss Armageddon and explain how Bay changed my perception of action films.

If it helps you to relate to my position at all, I’ll admit that I was skeptical about the movie going in.

First, it was the second giant-rock-destroys-Earth movie of 1998 (it was a comet in Deep Impact). Believe it or not, this idea had been one that petrified me for nearly a decade.

In 1990 I read an article in the newspaper entitled “The Doomsday Rock” which described the likelihood that, eventually, a giant asteroid would collide with Earth and cause the extinction of the human race.

I had grown up with the fear of nuclear Armageddon ending our species, but by 1990 the Cold War was over and I could finally stop worrying. Now came an even bigger fear — at least nuclear war required two human beings to consciously kill everyone, but no one could control or stop a giant asteroid.

I kid you not; I didn’t sleep for days after reading that article. It became my biggest fear: death by asteroid. It’s a terror I’ve learned to live with, but every day I hope that NASA receives the funding it needs to track more of these objects in space; as even NASA’s chief Charles Bolden has said our only current hope is to “pray.”

While the concept was one that scared me, seeing two similar movies came out in the summer of 1998 seemed excessive. Deep Impact beat Armageddon to theaters by more than two months, and it was a deeply moving and touching film. By the time of Armageddon’s debut I thought we’d already seen all the giant rock movies we needed.

Before seeing Armageddon I could not imagine why an astronaut would need a gun. It’s one of the many improbable plot twists that I ended up going with.

Even more than that, Armageddon‘s pre-release press made the film sound absurd. While ostensibly a disaster film about a big asteroid, I read articles which mentioned scenes showcasing astronauts with handguns. In what world would a gun become instrumental when a giant rock is about to kill all life on Earth? Despite having Bruce Willis as the star, this wasn’t Die Hard; what role would guns play? The astronauts in Deep Impact didn’t need them.

Despite those reservations I still found myself in a packed theater during the film’s Fourth of July opening weekend.

I was drawn in by several factors, starting with director Michael Bay.

Bay had impressed me with Bad Boys, which I thought was the best buddy-cop film since Lethal Weapon, and it marked the first time I saw Will Smith as a movie star. Bay’s follow-up, The Rock, was loud and heavy on explosions, but had some great action scenes for Sean Connery and Nicolas Cage.

And, for the longest time, I thought Bay also directed Cage in Con Air, which was dumb fun. I was likely confused by the fact that Jerry Bruckheimer produced both films. So, despite Bay having no involvement in Con Air, it was still a factor in my seeing Armageddon.

A larger factor pulling me to the theater was the cast. I had been a devout fan of Willis since Moonlighting. I loved seeing him in film; it didn’t matter if it was Color of Night, North, Pulp Fiction, Nobody’s Fool, or even Hudson Hawk.

Next was Ben Affleck, an actor I knew from his work with Kevin Smith, plus his Oscar-winning screenplay for Good Will Hunting. This was his first big-budget epic, and as he was a friend of Smith’s I was rooting for his success.

The rest of the cast — the ragtag group of asteroid drillers — was made up of some of Hollywood’s best 90s character actors, including Billy Bob Thornton, Steve Buscemi, Michael Clarke Duncan, Owen Wilson, and Keith David. I was even happy to see Ken Hudson Campbell, an actor I fondly remembered from his role as the “Animal” emotion in Herman’s Head.

While many of those stars would be launched to greater fame by Armageddon, even in 1998 I thought of this as a “dream team” of performers.

It was very lucky that I did know this cast, as I quickly realized that in Armageddon they were not characters, they were “types.” Affleck was the young hotshot, Buscemi the sardonic genius, Wilson the funny one, Duncan was the big guy who was soft on the inside, and Willis was the tough-as-nails, no-nonsense leader of the pack.

The baggage I brought with me from previous films helped me tremendously, as Armageddon wasn’t going to spend a lot of time developing new relationships or exploring character emotions. This movie was going to put the pedal to the metal and go, go, go.

It opens with a meteor shower demolishing New York City, and from that moment NASA is racing the clock to save humanity. The pace is so fast, Bay never stops the film to let the audience catch its collective breath.

Initially I was put-off by this; here was a movie exploring my deepest fear, yet the characters on screen never worried. They’re laughing, drinking, going to strip clubs and spending money like there’s no tomorrow — because there might not be. What a tonal shift from the dour Deep Impact. Even when we weren’t dealing with the asteroid directly, there were few scenes that didn’t involve a fight or a chase.

When we are introduced to Willis’ Harry Stamper he’s chasing Affleck through an oil-drilling platform, the older man shooting at the younger one. The reason for this homicidal rage? Affleck’s character, A.J., was caught sleeping with Harry’s daughter, Grace (Liv Tyler), and Harry hoped she would do better than a roughneck like her father.

It’s silly. It’s outrageous. It’s over-the-top. I wasn’t sure if I was going with it at all. My consternation only increased as the movie continued through the training montage and other silliness.

It wasn’t the concept of “only the best oil drillers in the world can save us” that put me off. That was standard fish-out-of-water storytelling. Think back to The Last Starfighter, where only a teenage video game player can win an interstellar war. Or in 48 Hours, where a cop needs a convict to catch a killer. Even in The Terminator a waitress had to fight alongside a warrior. This “you’re the only one, even though you’re unqualified” trope was one I’d grown up with, though never witnessed to this extreme.

My problem was I had no idea who these characters were. In a rare slow scene A.J. and Grace enjoy a final picnic, and some erotic animal cracker play, before his spaceflight. When asked if he thinks anyone else is doing that same thing at that time, A.J. responds, “I hope so. Otherwise, what the hell are we trying to save?”

It was a question that resonated with me — in a film full of cardboard characters, why did I care if everyone died?

It started to click, though, in another pre-spaceflight scene. Driller Chick (Will Patton) goes to see his ex and their son. The son doesn’t know his daddy, and a dropped line about a court order implies Chick hasn’t been the best father. But in this moment, at the end of the world, Chick wants to give his son a toy space shuttle. This was a character with very little screen time and no distinguishing characteristics, yet, out of the blue, suddenly he has a backstory: a son, and his own regret.

This is when I had my “eureka” moment. How many times have I seen this story of the estranged father who, just before a moment of heroism, reconnects with his child? Or vice versa? It’s a moment intended to endear us to the character and show an emotional connection, a reason for them to live, or motivation for them to sacrifice themselves.

Be it Nancy saying goodnight to her mother in A Nightmare on Elm Street, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s tender reconnection with Alyssa Milano in Commando, or even Willis’ own Die Hard where he leaves a message of regret for his wife and children, we’ve seen this time and time again. (We’d see an echo of it later in Armageddon between Harry and Grace as well).

The difference is that in those other films the moment is the climax of an emotional relationship, recognition of clarity and regret. But for Chick this is the first sign of characterization he’s given. Did we know he was a bad dad before this second? Did we care?

Through Chick’s sudden storyline I realized this wasn’t a film in the classic sense, it was a two-and-a-half hour music video. The vibe is the same — rollicking rock music (mostly classic rock by ZZ Top and Aerosmith) blared through the theater’s sound system while the characters underwent mental health evaluations and simulated spacewalks.

There were so many Aerosmith songs I wondered if the band (fronted by Liv Tyler’s father Steven) was chosen because Liv was in the movie, or if Liv was in the movie in exchange for Bay being able to raid Aerosmith’s catalog.

Even when the characters go to space and the rock music stops, the bombastic score takes over and keeps the vibe going. But more than just being driven by music, the storytelling methods in a short video and Armageddon are identical.![]()

In a five-minute song there is little time to create a unique character, so tropes and types must be utilized to tell a story.

In Michael Jackson’s “Beat It” I don’t need to know the gang members have families and loved ones, I can bring that to the story myself. In Aerosmith’s “Cryin’” video I don’t need to hear a word to understand Alicia Silverstone is a rebellious teen. I didn’t need to see the kid picked on in school to know he’s a geek in the video for The Offspring’s “Pretty Fly for a White Guy.”

Bay came from music videos, and he trusts the audience to be used to this shorthand storytelling and rapid cutting. This movie was aimed directly at those weaned on MTV. If we have already seen scads of movies that embody a trope, why recreate it?

That’s when it hit me; Bay wasn’t lazy, he was efficient! He trusts his audience to have seen movies with these characters in them before, and thus he can actually get away with just putting tropes in a scene and letting them have their action. Characters can be types instead of people, in a movie that isn’t really about the people anyway.

I already hear, in my own head, the counter of that — that movies should be about people, and that if we don’t care about the characters how can we be excited by the action. It’s an argument I’ve used myself when discussing some of Bay’s later Transformers films.

Yet, I do believe that there should be balance. If all movies were the same, a cinema would be a mighty dull place to visit. There should be room for different types of stories. While two 1998 films told the story of a calamitous collision that ends life on Earth, the way the stories were told make those films as different as night and day.

But, and I cannot stress this enough, what Bay is doing is a tightrope walk. It is a dangerous game to rely solely on hackneyed plots and character tropes. Here, he pulls it off, in large part due to an extraordinarily likable, talented cast that brings more to the screen than they were given on the page.

The director must be given credit here as well. The editing, camerawork, and special effects were all top-notch. Bay knew how to film a scene for maximum adrenaline, and the music made it feel like a party.

Bay’s go-to image for pride is a giant American flag. It’s not subtle, but there’s no denying it plays in the heartland.

Who knew the end of the world could be so fun?

The film does overstay its welcome, especially in the longer Criterion Collection Director’s Cut where Chick’s same story beat is repeated with Harry visiting his father in a nursing home. Yet, for all the crazy twists and turns the plot takes — and the obvious heartstring-tugging climax — Armageddon is a fun ride. I walked out of it knowing I enjoyed the movie, though I didn’t respect it very much.

As Bay has continued to make movies Armageddon has become harder to defend. With three abysmal Transformers films, plus Pearl Harbor, he’s too easy a target for us critics to hit. Transformers especially took the storytelling methods of Armageddon to their worst extreme, invoking tropes in ways that I didn’t give a damn about.

You can hear my detailed thoughts on those three awful films, plus the fourth not-too-bad one, in the Now Playing Podcast archives.

I may be mostly drawn to films that do provide insights into characters and comment on everyday life though on-screen events. But sometimes I just want escapist entertainment. Armageddon delivers that in spades.

Tomorrow — 1999!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 28, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1990s, Action, adventure, Aerosmith, Armageddon, Ben Affleck, Bruce Willis, Enertainment, Film, Michael Bay, Movie, Movies, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, sci-fi | Comments Off on The 40 Year-Old-Critic: Armageddon (1998)

40 Year-Old-Critic: Chasing Amy (1997)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

Kevin Smith is a polarizing figure in cinema. The director certainly has his legion of fans, and having attended several conventions with Smith as a featured guest, it seems those fans are mostly male, mostly under 30, and very willing to connect with his characters; lovable losers such as Clerks’ Randall and Dante (Brian O’Halloran and Jeff Anderson, respectively).

I am not in Smith’s camp, and on Now Playing Podcast I have repeatedly expressed my disdain for his body of work.

Yet allow me in this entry of The 40-Year-Old Critic to praise Smith’s best film, 1997’s Chasing Amy.

Amy (as some fans refer to it) was Smith’s third picture. The director was a Sundance phenom with his black-and-white debut (the aforementioned Clerks) in 1994. It did well in theaters and truly found its audience on video — an audience that included me. Thanks to Quentin Tarantino and Reservoir Dogs, I was paying more attention to indie films, especially those heavily promoted by Miramax. As such, I saw Clerks on VHS and enjoyed it.

As I mentioned in my review of Leaving Las Vegas, around this time in my life I was underemployed and frustrated with my lack of career options, so I related heavily to Dante in Clerks. Plus, I was enraptured by the raunchy jokes. Smith raised the bar on profanity with language that originally earned his film an NC-17 rating. As I did with Beverly Hills Cop before it, I laughed loud and hard at Clerks’ envelope-pushing comedy.

Smith parlayed that success into a studio picture, 1995’s Mallrats. The director spent $6 million of Universal Studios’ money on a movie that barely made one-third that amount. Even as a fan of Clerks I thought Mallrats was too cartoonish, too broad. With new lead duo Brodie Bruce and T.S. Quint (Jason Lee and Jeremy London, respectively), Mallrats tried to replicate the bromance of Clerks in a way that felt forced. More, it seemed Smith’s signature characters of Jay (Jason Mewes) and Silent Bob (Smith himself) would not work in color.

Mallrats would not be Smith’s last failure, but it may be his most fortuitous. First, it established his relationship with Ben Affleck, who had a minor role. Second, after Mallrats Smith returned to his “comfort zone” of small, indie filmmaking. On a $250,000 budget — extraordinarily low but still 10 times that of Clerks — Smith wrote and directed Chasing Amy.

By 1997 I was fully indoctrinated into the Cult of Kevin — as rabid a fanboy as any he’s had. I participated in his online message boards and I watched his first two films regularly (and convinced myself Mallrats wasn’t that bad… it is). Whatever Smith made next I would see. Yet the plot of Chasing Amy I found particularly interesting.

Alyssa (Adams) literally comes between Holden and Banky in this scene.

The film centers around two young independent comic book creators, Holden McNeil (Affleck) and Banky Edwards (Mallrats’ Jason Lee). The best friends find their relationship strained when Holden begins a romance with lesbian comic creator Alyssa Jones (Joey Lauren Adams; Smith’s then-girlfriend), spurring jealousy in Banky.

To me, the film seemed to be jumping on the bandwagon of “queer cinema” which had started to gain steam in the mid 90s. While mainstream Hollywood acknowledged gay characters in movies like Philadelphia and The Birdcage, it was really indie films that brought them to the fore, with such groundbreaking fare as My Own Private Idaho, The Crying Game, and Kiss Me, Guido.

Specifically, I saw in Chasing Amy echoes of Guinevere Turner’s Go Fish — a film Smith acknowledges as inspiration. Sexual preference felt like an exciting new frontier for films to tackle and, having seen all the ones I just mentioned, I likely would have seen Amy even with a complete unknown behind the camera.

I was actually a bit nervous to see Smith tackling LGBT topics. This was a straight man with a penchant for raunchy humor. In Clerks, for example, lead character Dante slut-shamed and dumped his girlfriend after finding out her sexual history. I wondered if Smith would use Alyssa’s sexuality as a source of humor, or to titillate his built-in male audience.

I was happily wrong. Chasing Amy is an exquisite balance of comedy and drama. The start of the film is right in line with Clerks’ humor, as militant black comic creator Hooper X (Dwight Ewell) dissects the racist undertones of the Star Wars trilogy. It was great fun, like a geeky twist on Tarantino’s Like a Virgin deconstruction in Reservoir Dogs. But the humor is nuanced. It’s quickly revealed that not only is Hooper’s rage an act to sell his comics, but he is also a closeted gay male and close friend of Banky and Holden.

As Holden and Banky, Affleck and Lee created a genuine on-screen friendship. It was one my friends and I related to…until the final twist.

The latter two characters would be familiar to Smith, and not just because both Affleck and Lee appeared in Mallrats. In Clerks, Mallrats, and again here, Smith features the same central duo: immature twenty-something white males with potty mouths. The primary character is more serious, contemplative, semi-neurotic, and dealing with relationship issues. The sidekick is wacky, always given the movie’s funniest lines, but given short shrift in the plot. Here, Holden was our Dante/Quint, and Banky was our Randall/Brodie. The jokes were raunchy and familiar, and the laughs hit hard.

More, Smith seems to know his audience. Any homophobes in the theater get their say through Lee, who spouts gay slurs and stereotypes throughout the film. Featuring gay characters in a positive light, and having Banky spout ignorance, was a subtle way of Smith attempting to educate a more narrow-minded contingent of fans.

Chasing Amy slowly changes tone, though. While all of Smith’s films had dealt with romantic relationships, none had been a romance film. Amy becomes that as Holden befriends unobtainable Alyssa. Their friendship is tinged with longing, and not just on Holden’s side — Alyssa’s feelings for a man make her question her own sexual identity. The scene where Holden confesses his feelings, followed by a rain-soaked argument, is moving and engrossing. There is barely a laugh to be had, and shows a maturity not before seen in a Kevin Smith film.

The film takes continued twists and turns, and jokes keep coming, but Smith had sharpened his humor into a blade, using it to cut the tension of many tense, dramatic scenes. The audience, engrossed in this tumultuous relationship full of self-doubt, would find their laughter a welcome release — the film allowing us to breathe again.

This kiss in the rain was Alyssa finally giving into her feelings for Holden. In most films that would be the end, but here it’s only the beginning of a journey full of self-doubt and jealousy.

While the romantic comedy fan in me was enjoying the Holden/Alyssa relationship, I was also empathizing greatly with Lee’s Banky. I was in my mid-20s and I had lost many friends to their girlfriends. I was all-too-familiar with the pattern of friends who hang out when they’re single, and then don’t return your calls when in a relationship. I saw Banky losing his lifelong friend to a new relationship, and, for the first time ever in a Smith film, I felt bad for the sidekick. Smith had finally created a supporting character with his own arc.

Holden and Alyssa’s relationship eventually hits the rocks when Holden finds out Alyssa was not always gay. The climax (so to speak) comes when Holden, desperate to save his friendship and his relationship, proposes a three-way to both Alyssa and Banky.

That was where the film took things too far. Until that point I felt Smith’s film had portrayed characters acting in ways that felt honest. This twist seemed to be the writer/director choosing to go with a wacky ending over a heartfelt one, or maybe he just wrote himself into a corner and couldn’t find a more earnest resolution.

The group sex idea felt totally outside the realm of Holden’s character. More, that Banky agreed, seemed to me a full character betrayal. I had completely understood Banky’s disappointment with a friend ditching him for a new relationship — it’s a real, common occurrence among single male friends. That Smith chose to write that entire emotion as based in latent homosexuality felt like a missed opportunity — an honest look at friendship was undermined by turning one character into a stereotypical gay male predator.

The film does recover from that moment, with an ambiguous ending that reminded me of The Graduate. Despite my disappointment with the final twist, the movie overall remained an on-screen romance that came across as honest and real. I left the theater entertained and believing Smith would be the next great voice of cinema.

He tried. His follow-up film, Dogma, attempted to analyze religion the way Amy deconstructed relationships, but to lesser effect. While amusing, the picture is scattered and scatological.

But it was with his next effort, Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, that I realized Smith was not an auteur with things to say, but a writer of increasingly insipid comedy. I first saw Smith speak at a convention in 2001, followed by a preview screening of Strike Back, and I realized he was a more amusing speaker than filmmaker.

History would prove that assumption true, as Smith is now an accomplished podcaster, while the best thing I can say about his post-Strike Back films is that there aren’t many of them.

I have seen all of Smith’s directorial efforts, always hoping to see even a hint of the filmmaker that made Chasing Amy. But from Jersey Girl to Zack and Miri Make a Porno to Cop Out and even Red State, Smith has become a serviceable, but completely unexceptional, director of (mostly unfunny) comedies. I would characterize Smith’s later directing work as on par with Tom Shadyac or Steve Carr. If you don’t know those names, you can look them up, but had Smith not been an indie darling in the mid 90s I don’t think you’d know his name either.

I don’t mean that to say Smith is a one-film-wonder, still coasting on Clerks, because I have gone back and watched his directorial debut — it doesn’t hold up. Jokes that pushed the envelope in 1994 now seem almost tame. More, Clerks is less a film than it is a series of sketches loosely tied together. I loved it when I was the characters’ age and related to their Generation X angst, but it is a movie with limited appeal that is quickly outgrown.

I had hoped that after Cop Out’s critical drubbing Smith might — as he did after Mallrats’ failure — return to his roots and make more personal films. That hasn’t happened. While he has done more low-budget films, such as Red State, it appears the filmmaker who made Chasing Amy is gone forever.

It is a shame. With Chasing Amy Smith showed himself to be a talented writer who could balance both comedy and drama with equal measure. It remains a go-to film when I want to laugh, one of the most honest romances caught on screen, and a progressive view of LGBT characters in cinema. Yet it’s the only Kevin Smith film I can recommend.

Tomorrow — 1998!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 27, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1990s, 40-Year-Old Critic, Ben Affleck, Chasing Amy, Comedy, Comic Books, Comics, Drama, Enertainment, Film, GLBT, Jason Lee, Kevin Smith, Lesbian, Movie, Movies, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Romance, Romcom | 2 Comments

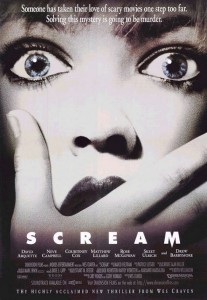

The 40 Year-Old-Critic: Scream (1996)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

What’s your favorite scary movie?

As I mentioned in previous reviews of Love at First Bite and Hellbound: Hellraiser II, I have always been a horror fan.

As a very young child I loved the fear I felt toward forbidden cinema, and as I aged I came to see the humor, thrills, and scares in the genre. In my 20s, though, my love of horror changed. I had grown up and no longer had exciting nightmares starring Freddy Krueger. To me, there were no more mysteries in the world, and no more scares to be had on screen.

This problem was exacerbated by a lack of exciting horror in theaters. The slasher craze of the 80s had waned with Friday the 13th Part VIII: Jason Takes Manhattan and Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare. By the early 90s the genre seemed to be gasping its last breaths; Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday was the 1993’s top-grossing horror film with only $15 million — nearly tying Manhattan’s $14 million for a series low. A year later the only notable horror release in theaters was Wes Craven’s New Nightmare. By the time The Mangler and Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers came and (quickly) went, it seemed the bloody fun of the cinema was gone.

At the same time Hollywood was failing to launch new horror stars on screen. The first Leprechaun was released to little fanfare, and audiences simply laughed off Dr. Giggles.

I still enjoyed horror where I could find it, but that was mostly on direct-to-VHS releases. There was the occasional gem, such as Return of the Living Dead 3, or Tales from the Crypt Presents Bordello of Blood, but it was largely a parade of dreck.

I thought horror was dead.

But like any good villain, horror came back from the dead in the holiday season of 1996. The best gift I received that Christmas was an unexpected revival! Suddenly horror was cool again, and the film that made it happen was Scream.

If Ghostface had narrowed the scope to “What’s your favorite scary movie from 1990 to 1995” I think his victims would still be trying to find one.

Even though I’d let my Fangoria subscription lapse, I’d kept up with horror film production in the 90s. I knew that Wes Craven, creator of the A Nightmare on Elm Street franchise, was working on a new slasher film… and I wanted nothing to do with it.

Though I idolized Craven growing up, due exclusively to the Nightmare series, the director’s later works were crap.

I was unimpressed and felt betrayed by Craven’s incoherent and bloodless 1989 slasher Shocker — though I have since come to love the film for the over-the-top “schlocker” that it is. Then in 1991 I raced opening weekend to see The People Under the Stairs, and was simply bored.

I still didn’t learn. I became ecstatic when I heard Craven’s next film would be a return to the Elm Street series, the director promising to make Freddy frightening once again. When I walked out of Wes Craven’s New Nightmare I felt I had seen my last Craven film. You can hear my full New Nightmare review in the Now Playing Podcast archives, but I truthfully wondered how I ever idolized this man who seemed able to only make terrible movies.

That line of thought was cemented with 1995’s Eddie Murphy horror comedy Vampire in Brooklyn, a film I saw out of devotion to Murphy, not Craven.

So in 1996, hearing Craven was going to make a new horror film was actually a turn-off. In ‘96 I would have rather gone to theaters to see Lawnmower Man 2: Beyond Cyberspace than Craven’s Scream.

Scream turned Barrymore into an A-list star once again.

The cast did nothing to change this impression. Press materials touted Drew Barrymore’s role, and that seemed a bad sign. Back then she was still the little girl from E.T. who, like so many child stars, had developed a dependency problem. While I had seen her work in Boys on the Side and Mad Love I thought her heyday was behind her; the only roles she had in major releases were bit parts in Wayne’s World 2 and Batman Forever. She seemed “over” in Hollywood. I would never have guessed that, thanks to Scream, Barrymore was poised for a return to superstardom.

The rest of the cast — actors I’d not heard of or knew only from television shows — also failed to grab my attention. The only cast member that caught my interest was Matthew Lillard, whose zany performance I’d loved in Hackers, yet that was not near enough for me to want to see this movie in theaters.

Most of all, the film’s trailers didn’t hook me. I thought the killer’s mask was silly — had Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees taken all the good killer masks? I admit I was intrigued by the thought of characters that knew horror movie tropes; I mean, this was a horror movie where the characters were people like me. Still, with Craven’s name on the poster I wanted nothing to do with it.

Lillard would go on to the Scooby Doo films after himself being unmasked as the bad guy in Scream.

I saw Scream in theaters only because I was invited by a group of friends and my options were to go to this movie or stay home alone. I wasn’t happy about going, and I anticipated a wholly miserable People Under the Stairs type of experience.

To say I was won over is an understatement. The film did have a good deal of true horror, with the opening murder scene a suspenseful highlight. With the scares firmly established, the movie achieved a near-perfect balance between self-referential humor and legitimate tension. While, due to my age, I was not afraid, the film did succeed in making me jump a couple of times.

In 2011 I gave my full review of Scream as part of our retrospective series leading up to Scream 4, so I will not repeat myself here. You can listen to that full review for a blow-by-blow analysis by Stuart, Marjorie and myself.

In short, not only did Scream win me over; I feel it is Craven’s best film — even better than my beloved A Nightmare on Elm Street.

I believe Craven was greatly assisted by the script from first-time screenwriter Kevin Williamson. Having seen many films made from Craven-penned scripts, none come near Scream in terms of plot twists, fleshed-out characterizations, and careful plotting. The movie was a whodunit, something I didn’t expect in a slasher. After all, in most slashers I knew the killer was Freddy or Michael or Jason or Chucky. That the killer was one of the kids was a fun experience — me trying to outwit the characters and peg the killer. When the mask is removed and the full story revealed, even I was taken aback by some of the twists. This is all Williamson, and I give him full credit for the film’s quality.

I watched Friends, but never saw Cox as a good fit for horror. Again, I was wrong.

Yet I cannot overlook Craven in the director’s chair. While the script was great, Craven brought two decades of horror experience to Scream. He knew how long to hold a moment, how to reveal a body, and how to build tension that would climax with a jump scare.

My heart was racing as I left the theater. This was the first great original horror film I’d seen in many years, yet had I known the long-lasting impact Scream would have, my exuberance would have been even greater.

The movie went on to make nearly $175 million on a $15 million budget, reminding Hollywood that a good horror movie can provide substantial returns.

Scream single-handedly revived the entire horror genre. The next year gave us not only Scream 2, but also — thanks to Williamson’s success — the enjoyable, but forgettable, I Know What You Did Last Summer.

We also got the Wes Craven-produced Wishmaster, which I saw in theaters and found a weirdly awful throwback to the days of Leprechaun.

By 1998, other studios had caught on and the post-modern, self-aware horror film had its heyday with Bride of Chucky, Halloween H20, Urban Legend and The Faculty. The quality was mixed, but all were far better films than Lawnmower Man 2 or The Curse of Michael Myers.

Scream made me appreciate Craven’s ability, but even more its success spawned dozens of films I’ve enjoyed over the past 20 years. For that reason alone, if not just for the movie itself, Scream might just be my favorite scary movie.

Tomorrow — 1997!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 26, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1990s, 40-Year-Old Critic, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Enertainment, Film, horror, Kevin Williamson, Movie, Movies, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Scream, Slasher, Wes Craven | Comments Off on The 40 Year-Old-Critic: Scream (1996)

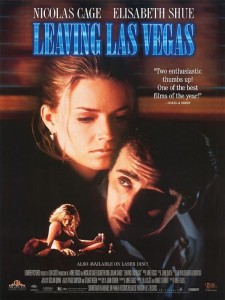

40 Year-Old-Critic: Leaving Las Vegas (1995)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

Have you ever had the feeling that the world’s gone and left you behind….

More than any other form of art, films have a soul. Moviegoers can experience a picture on more than an intellectual level; sometimes there is a base, emotional connection. Watching a great film can be akin to falling in love.

This is a view I first articulated while reviewing Gus Van Sant’s 1998 remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho for Now Playing Podcast (part of our Fall 2012 donation drive, that review is no longer available). That film showed two talented directors could take the same script, sometimes even the same camera shots, and produce different results. One filmmaker created art that engrossed and thrilled audiences, while the other produced a rote, mechanical and generic film.

Tens, hundreds, or even thousands of people — depending on the scope of the production — come together to create a single experience for a viewer. Even I sometimes forget this; the auteur theory takes hold and I focus on the director as sole creator of a vision. While the director usually maintains creative control, sometimes even through the editing stages, the movie itself is the result of millions of little decisions made by every actor, set dresser, composer, editor, and cameraman on the production. With the right people involved even the most mundane script can become a memorable experience.

One prime example of such a script elevated by those working on it is Leaving Las Vegas, the 1995 drama directed by Mike Figgis, starring Nicolas Cage and Elisabeth Shue. On paper, this movie seemed like the most trite of stories — depressed drunk Ben Sanderson (Cage) is a Hollywood screenwriter whose penchant for drink has ruined his every personal and professional relationship. When he is finally fired from his job he is ready to die, so he takes the last of his cash to Las Vegas where Ben plans to drink himself literally to death. In Vegas Ben hires a prostitute Sera (Shue), the damaged hooker with a heart of gold. The two lost souls fall in love, yet neither is willing or able to change their self-destructive habits.

These character tropes are so hackneyed that I would expect this to be a film made in the 1930s, when stories and characters were broader, and not the 1990s.

Cage in one of his more charming scenes, back-lit by the lights of the Vegas strip.

The film is based on a novel by John O’Brien. I have not read that book, but I have no doubt of O’Brien’s commitment to the material. Two weeks after discovering Leaving Las Vegas was to become a film, O’Brien used his gun to commit suicide. Clearly this was a man who understood the struggle with depression and the impulse to kill yourself. Yet, despite the insight his prose may offer, I have no interest in reading a book about two stereotypical characters going through a depressing endeavor. It may be very well written and I may be missing out, but the story itself sounds uninteresting.

Yet, despite cliched characters and a tired plot, in the hands of these filmmakers the result is a dramatically moving experience. Few movies I’ve seen in my life parallel the emotions stirred in me by Leaving Las Vegas, for what this team did, through filming and editing, was craft a film where the plot matters less and the characters matter more.

The tale is about a drunk, and the editing and filming often give the film a fugue-like ambiance. Sometimes the dialogue is crystal-clear, loud and in full focus. Other times the music mix raises. Sometimes you hear nothing as the actors’ lips move, other times there are words but you cannot make them out. It’s a dream-like experience that reminds me of techniques used by David Lynch.

The impact of the music cannot be overstated. The score, composed by Figgis himself, sounds like music played around 2 a.m. at an upscale bar. Heavy with piano and saxaphone, the music has a slow jazz feel that underlines the emotions of the moment. More, in an unusual move, some of the score is lyricized and sung by Sting. It blurs the line between soundtrack and score, but in the process creates sorrowful ballads of love and loss. Those original compositions intermix with covers of classic songs, such as “Lonely Teardrops” sung by Michael McDonald.

The sounds of the street often drown out character dialogue, to great effect.

The result sometimes feels like a depressing music video or an “in memoriam” montage, played while the characters still live. That Figgis is so willing to part with dialogue and just convey mood shows that in Las Vegas plot doesn’t matter. This is a character-driven story and we don’t need to hear their words to feel their pain.

This type of disregard for traditional narrative is used at the micro and macro scale. Sometimes the film cuts to the future suddenly, and we return to the present when Ben comes out of his stupor. We learn about the missing moments when Ben asks what happened. This is a movie told primarily from Ben’s shaky, out-of-focus point of view, and the camerawork and editing embody that mindset.

More than the cinematography, this film hops in and out of Ben’s own head. Sometimes we see Cage saying outrageous things, but then we discover it was only a fantasy in the character’s mind. In contrast, sometimes Ben makes equally offensive statements out loud and faces the very real consequence. As his blood alcohol content rises Ben cannot distinguish reality from fantasy, and, like Ben, the audience never knows exactly what is happening and what we can believe.

Of course, Figgis could not accomplish this alone. In the hands of a lesser actor than Cage Leaving Las Vegas could become an unintentional comedy quickly forgotten. Now, 20 years later, Cage is often disregarded, written off due to a long string of bad movies in which the actor makes unfortunate character choices.

Cage is an actor who gets off on playing characters in unconventional ways and giving them strange mannerisms. Often that will alienate the audience, but in Leaving Las Vegas Cage commits totally to the role. His body language exudes desperation. In one of the movie’s first scenes Ben is unintentionally sober, craving drink, and hitting up some colleagues for cash. He comes off sweaty, clumsy, and off-putting. One scene later, after a few drinks, Ben has an undeserved, over-inflated sense of self-confidence and makes improper advances on an attractive woman at the bar. It’s a wild swing of character, and is played perfectly through Cage’s intonation, eye work, and mannerisms.

This type of character could alienate audiences. Had viewers seen Ben as more creepy than sympathetic the result could be quite different. It’s little moments Cage plays, such as sobbing “I’m sorry” when being fired, that show humanity in this sad soul. It makes him someone we feel for, rather than pity.

I was a fan of Cage’s coming into Leaving Las Vegas, with Guarding Tess, Trapped in Paradise and Wild at Heart as highlights (though I’d also suffered through Kiss of Death, It Could Happen to You, and Amos & Andrew). Cage often gave captivating performances, but none I’ve seen before or since match his Oscar-winning performance here.

Despite how they meet, the relationship between Ben and Sera is about love, not sex.

Matching Cage’s portrayal is co-star Shue. In her roles in Back to the Future 2, Adventures in Babysitting, and even Cocktail I’d found the actress to be capable, but unexceptional. As Sera, Shue shows a range I’d never seen before. Early in the film Sera is a hooker, and very good at her job — she instinctively knows what the John wants, and becomes it. With Ben we see Sera start to open up. She lets down her guard, takes off her make-up, and becomes a real person. The transformation is startling, as is Shue’s lack of vanity in several unflattering scenes.

But Sera is not your normal streetwalker — she also has regular visits to a therapist. In these scenes we get to see inside Sera’s thoughts through monologues, confessions taken from her therapy session. As edited, these moments play like scenes from the confessional booth in MTV’s The Real World, but without them we would never be able to trust Sera. We never see the therapist; Shue is giving brief one-woman performances, but conveying pure emotion. This is a challenge for any actor, and she pulls it off. Shue fully deserved her Academy Award nomination for this performance.

Together Cage and Shue create a wholly believable, wholly dysfunctional, couple. Both broken characters are instantly drawn to the other. Though Sera knows Ben may be trouble, she puts that aside and chooses to follow her heart. The film avoids making their relationship too gross or base by actually, and believably, removing sex from the equation–while Ben hired Sera for physical gratification the liquor prevented him from performing. He becomes the only character not sleeping with Sera, even choosing to sleep on the sofa at night despite Sera’s repeated offers of more.

These two share a chemistry and a spark on screen that few romantic films can match. Though it’s a futile hope, it’s easy to root for these two to overcome their hardships through their new-found love.

Those two actors are the primary cast but even the minor roles are perfectly played by actors you’ll recognize; from Steven Weber (Wings, Stephen King’s The Shining), to comedian Richard Lewis, to Laurie Metcalf (Scream 2, Roseanne). It could almost be a drinking game — take a shot when you see an actor you know. With French Stewart, Shawnee Smith, R. Lee Ermey, Mariska Hargitay, and even, in the thankless role of bank teller, License to Kill’s Carey Lowell, you would be as drunk as Ben when credits roll.

No one on screen breaks the mood. Figgis has created his own Vegas, sometimes romanticized, sometimes demonized, but always real.

Leaving Las Vegas is a film with layers. On the surface, taken literally, the plot is about a terminal man and the woman who loves him as he dies. In such a bland interpretation, Sera is nothing but a fantasy, a female who serves a man’s needs. Sera describes herself as being instinctively able to become what her clients want, and she does that for Ben. Early in the film the drunk fantasizes of a woman pouring liquor on herself so he can drink off her, and she would have purpose. Ben never tells that to Sera, but she does that for him — alcohol and sex, Ben’s fantasy realized. Ben calls Sera, “my Angel”, and you could see her as nothing but.

Leaving Las Vegas is a film with layers. On the surface, taken literally, the plot is about a terminal man and the woman who loves him as he dies. In such a bland interpretation, Sera is nothing but a fantasy, a female who serves a man’s needs. Sera describes herself as being instinctively able to become what her clients want, and she does that for Ben. Early in the film the drunk fantasizes of a woman pouring liquor on herself so he can drink off her, and she would have purpose. Ben never tells that to Sera, but she does that for him — alcohol and sex, Ben’s fantasy realized. Ben calls Sera, “my Angel”, and you could see her as nothing but.

Yet to take that interpretation is to miss several important details. Sera is, in many ways, a mirror of Ben. Both came to Vegas from Los Angeles. Both are recently unemployed (Sera finding herself without purpose when Yuri, her lover and pimp played by Julian Sands, is murdered by Russian mobsters). Both characters are deeply wounded and on dangerous paths. And both accept each other unconditionally; Ben’s condition of being with Sera is that she never ask him to stop drinking. Likewise, Ben is accepting of Sera’s profession, knowing that she will continue to hook while he lives with her.

Finally, Ben’s course is a straight one. He starts and ends the film a drunk and he never waivers from his path of self-destruction. It would be nihilistic if his story was the only one in the film. Yet through loving Ben, Sera softens. The relationship forces Sera to mature, and she evolves from accepting her doomed relationship to trying to fix it, finally asking Ben to see a doctor. When Ben responds by bringing another woman home to her bed, she instantly kicks him out — she was not that strong when the movie began and she was working for Yuri.

Finally, Ben’s course is a straight one. He starts and ends the film a drunk and he never waivers from his path of self-destruction. It would be nihilistic if his story was the only one in the film. Yet through loving Ben, Sera softens. The relationship forces Sera to mature, and she evolves from accepting her doomed relationship to trying to fix it, finally asking Ben to see a doctor. When Ben responds by bringing another woman home to her bed, she instantly kicks him out — she was not that strong when the movie began and she was working for Yuri.

The star of the movie is clearly Cage as Ben, but every time I watch this film I become more convinced the true main character is Shue’s Sera. And it is through Sera that I found my own redemption in 1996.

That summer I had graduated college. My Communications degree and B-average in were not opening any doors. I had a small apartment in a boring town. Most of my friends had left for bigger cities and greater opportunities. My full-time job was working nights as tech support for an Internet company. It didn’t demand much; I sat alone in an abandoned building for eight hours a day, answering the phone on the rare occasion that it rang. It also didn’t pay much; I was living on $8.25 per hour.

Not that I had career aspirations. In college I spent my time doing my coursework and never got to the other things I wanted to do — write some screenplays or even publish some short stories. I had nothing to build my resume, and no idea what career path I should take. I still wanted to entertain people — that drive instilled since seeing Pump Up the Volume — but come fall, even my gig as a DJ would be taken away.

Despite having family living in my same town, we were never close. I preferred being alone in my dark apartment to spending time with them (and I loathed being alone). I was so desperate for friendly contact that, despite having graduated, I asked my college radio station if I could continue to work (for free) as a DJ through the summer.

Mostly, I was lonely. While friends would have alleviated this problem, to me the solution was a girlfriend. Many of my college friends had married soon after graduation. It is very easy for a lonely straight man to envision a woman as the answer to his troubles, and I certainly fell into that mindset. Yet with few friends, no social events to attend, and Internet dating not yet commonplace, I had no way to even meet a woman unless she happened to be delivering my pizza one Friday night.

With all these troubles, no money, few friends, bad job, no prospects, I was suffering from a deep depression.

I was never suicidal, but my overriding emotion was one of apathy, with a side of hopeless despair. My only pleasure in life came from movies. I couldn’t afford to see many in theaters, but I spent what little surplus income I had at the rental store week after week.

Ben’s constant fight against DTs show alcoholism isn’t a glamorous way to die.

That was when I found a kindred spirit in Ben Sanderson. Despite having recently turned 21, I was never much of a drinker. Still, there was something romantic in the very notion of going to Sin City and dying through copious consumption.

Yet through this act of destruction, Ben found his “angel” in Sera. And despite connecting with Ben’s depression, in Sera I saw strength and hope. Sera was in an equally bad situation — her “career” was short-term and dangerous. She was a smart, attractive woman, and even the Vegas cabbies were telling her she could do better than her station in life. When the movie ends Sera loses her love but gains hope for a brighter future.

Through Leaving Las Vegas’ trippy mood, moving characters, and tale of redemption I found my own. I was inspired out of my funk. Nothing happened quickly, but over the next four years my ambition redoubled, I went back to school to get a more employable degree, and I met my wife. But when my future seemed nearly as bleak as Ben’s, Leaving Las Vegas showed me the neon light at the end of a tunnel.

I believe that connection is partially because of the tragic, sad story presented, but the experience is heightened by Figgis’ choice to drop out dialogue and scenes. Figgis’ music created an emotional call-and-response; when the film’s dialogue was drowned out my own struggles filled in the blanks. When the dialogue faded out I would project my pain into the film, mixing with Ben and Sera’s until we were indivisible.

Even today, as I live a much happier, optimistic, and realized life, the film still moves me. You don’t have to be in pain to empathize with those in pain; you don’t have to hear their words to know their struggles.

This is where Leaving Las Vegas transcends being a movie and becomes a full, engrossing experience. This is the soul of a film.

Tomorrow — 1996!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

August 25, 2014 Posted by Arnie C | 40-Year-Old Critic, Movies, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Reviews | 1990s, 1995, 40-Year-Old Critic, Alcohol, Alcoholic, Drama, Elisabeth Shue, Enertainment, Film, Las Vegas, Leaving Las Vegas, Mike Figgis, Movie, Movies, Nicholas Cage, Now Playing, Now Playing Podcast, Podcasts, Review, Reviews, Romance | 1 Comment

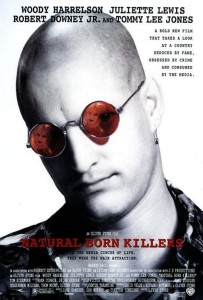

40 Year-Old-Critic: Natural Born Killers (1994)

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

Mister rabbit says, “A movie review is worth a thousand prayers.”

In 1994 I was in college with aspirations of filmmaking. While my university did not have a dedicated film curriculum, my Mass Media Communications major with a Creative Writing minor afforded me classes in screenwriting, film criticism, editing, camerawork, and more.

But as the major was not simply film, there were numerous other classes I had to take for my degree. The list included Communication Ethics, First Amendment rights, studies of media impacts on the audience, and journalism, to name a few. As a college junior, I lived and breathed my major. Every form of entertainment I enjoyed, from video games to television to books to film, was a subject for my college studies. I wrote papers and gave multimedia presentations on violence in film, with a special focus on the Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street franchises.

But that year produced something unexpected from Oliver Stone and Quentin Tarantino. I was used to films factoring into my curriculum, but I never expected a major motion picture to be studying the same topic.

Natural Born Killers did just that.

The story is pure Tarantino. Having rewatched both True Romance and Reservoir Dogs multiple times I instantly saw a familiar trope in Mickey and Mallory Knox — the killers/anti-heroes of this film. Seeing two young outlaws in love and on a crime spree seemed right out of True Romance. That they are also merciless murderers felt like an extension of some of the characters from Reservoir Dogs — Mickey and Mallory could be Mr. and Mrs. Blonde. Finally, the film has a non-linear narrative that ends in a Mexican standoff. Despite Tarantino distancing himself from the production I saw his fingerprint on the negative.

Despite the carnage, there was something pure and romantic about Mickey and Mallory’s love affair. It was sick and twisted, but also sweet.

I did later read the original script, which was published in book form. That draft was far more Tarantino, but still a reach for the director. More than a crime film, Tarantino’s Natural Born Killers had a pointed critique on American tabloid journalism.

Yet, in the hands of Oliver Stone, the film’s focus on the media grew exponentially. Stone, along with screenwriters David Veloz and Richard Rutowski, rewrote the script to the point that Tarantino ended up only receiving story credit. In the hands of Stone’s team, Natural Born Killers became a scathing commentary on American media.

It could not have hit at a more appropriate time. Rush Limbaugh was scoring big on radioand television with his daily indictment of the Clinton administration. Meanwhile the country was transfixed by the O.J. Simpson case. While this movie was released a few months before the trial began, the Ford Bronco chase and Simpson’s arrest were constant news.

The media focus seemed to go from one real-life drama to the next, be it Amy Fisher, Tonya Harding, Heidi Fleiss, the Menendez brothers, or even Woody Allen’s divorce from Mia Farrow — all were fodder for the newspapers and 24-hour news channels. What had once been the domain of the National Enquirer was suddenly considered “real news.” It seemed everyone was being given a talk show, and those who couldn’t host a show tried to get their 15 minutes of fame by appearing on one.

It’s ironic that Stone undertook this film as a chance to make a simple action picture, but he doesn’t do “simple.” As such, the result is an indictment not only of the media companies that propagate such coverage, but also the populace that consumes it.

Mickey and Mallory Knox, as brought to life by Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis, are products of the media. Despite Harrelson being in his early 30s when this film was made, Mickey and Mallory feel like members of the “MTV Generation.” These two realize they will never be TV stars, so they’ll be the next best thing: headline-makers. They guarantee it, always leaving one person alive to tell the media about Mickey and Mallory.

Stone has never been accused of being too subtle.

The journalists are not left untouched, though. The second half of the movie gets a shot of adrenaline in the form of Robert Downey, Jr., turning in a tremendous performance as tabloid TV reporter Wayne Gale. With an affected Aussie accent and an equally affected sympathetic persona, Gale convinces Mickey to do his first TV interview. As the film’s madness grows Gale starts to believe his own press, and eventually realizes the time comes when the audience wants to turn the TV off.

From the first frame to the last, Natural Born Killers is a film about the superficiality of personas, examining the concept of who a person is versus how he/she wants to be seen. While that difference is often greatest in the cases of public figures who must act a certain way in public but may be very different behind closed doors, the script shows that everyone has that secret face. The insight to that is Detective Jack Scagnetti (Tom Sizemore), who appears to be the heroic cop who brings down Mickey and Mallory. Yet the audience sees that he is a mirror image to Mickey. While Mickey kidnaps, rapes, and murders an innocent woman, Scagnetti hires, screws, and strangles a hooker.

Every character in the film is disgusting and immoral–save one Navajo Indian from whom Mickey and Mallory seek shelter. This character calls out blatantly that the two killers watch “too much TV.” While the mystical, magical medicine man is a blatant stereotype, he is the only character in the film who doesn’t deserve a bullet (but he gets one anyway). The police, the media, Mallory’s parents, even the random stranger Mallory seduces at a gas station, are all contemptible and repugnant.

In other words, they’re the product, creators, and consumers, of tabloid journalism.

Yet, for all of the high-minded idealism of the movie, Natural Born Killers avoids the usual “message movie” pitfall of heavy-handedness, which I discussed in my review of Philadelphia.

Stone’s filmmaking is too frenetic, too fast-paced, to ever linger. The film’s style changes with the scene; one moment we are seeing Mallory’s family portrayed as a sitcom, complete with laugh track, the next we have grainy black-and-white footage. There are even animated sequences inserted into the film that visualize the emotion of a scene. There is no way for the film to linger, there is too much going on.

Something as simple as projecting a slide on actors felt fresh among the ever-shifting styles in Natural Born Killers.

In that regard, the picture is a critique of its audience. Stone knew that moviegoers in the 1990s had short attention spans, so he created a film perfectly suited to the mindset of an ADD-addled channel-flipper. The story and characters remain the same, but the tone, even the film stock, continually change. Stone also inserts bits of real commercials, as if he holds the remote we’re watching him scan to see what else is on.

The result is a trippy, psychedelic movie that truly feels like a tonal companion piece to his 1991 film The Doors. Mickey and Mallory are also rock stars of the media, and they even seek guidance from the spiritual Native American.

Like that earlier Stone film, Natural Born Killers is an experience more than a narrative. The color pallette, the transition to animation, the first-person camera shots years before found footage films were en vogue, the result is less narrative and more emotional.

And like The Doors, Natural Born Killers is propelled by a strong soundtrack. While the former film was almost exclusively set to Jim Morrison’s music, it was limited by the subject matter. Natural Born Killers doesn’t have that limitation, and the styles of music represented are as scattered as the film techniques.

Stone collaborated with Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor to produce the soundtrack, and the result is a thumping, yet moody, symphony of discord. Music from Patsy Cline is interwoven with Patti Smith, Bob Dylan, L7, Dr. Dre, and much more — with a healthy dose of Leonard Cohen at the beginning and end.

Listening to the soundtrack is almost as involving an experience as watching the film. Reznor did not simply follow the Reservoir Dogs formula of putting film clips on the CD, he actually mixed it with the music, creating an aural cinematic experience.

(Though for those of us who are musical purists, it also ensured I bought many of the bands’ original albums to have versions of the songs without added effects and dialogue. It was this album that set me on the road to Leonard Cohen super-fandom.)

This entire tone could have been undercut by the lead actors, but Stone directed his cast expertly. All the leads, and key supporting characters, have left realism at the door. Exaggeration is the name of the game, so lines are screamed or drawled, movements emphasized, and facial expressions broad. Alone, that type of acting could undermine a film, but with the crazed visuals that accompany the scenes anything more natural would be lost.

The standout of the cast is Harrelson. Much like Tom Hanks with Philadelphia, I knew Harrelson from his comedies — not just Cheers, but Doc Hollywood, White Men Can’t Jump and even The Cowboy Way. I worried he could not pull off a performance as a homicidal maniac. More, as Harrelson was the son of a hit man who may have been involved in the John F. Kennedy assassination, it felt like stunt casting of the worst type.

Harrelson left behind his good-ol-boy persona and fully inhabited the homicidal persona of Mickey Knox.

I was again wrong as I watched Harrelson, head shaved, fall into the character. By the film’s climax — when he has to break the fourth wall and deliver the line “I’m just a natural born killer” — all thoughts of comedy were gone. He was just a bad-ass, homicidal, rock star.

His performance is clearly aided by those of his co-stars. Lewis, a quirky actress I first noticed with 1993’s Cape Fear, is perfectly cast as a psychotic who becomes empowered and emancipated by following Mickey’s murderous examples. Sizemore carries a sleazy menace that follows him to every frame. Even Tommy Lee Jones overacts to the heavens as the spiteful prison warden. The result is a cast in perfect harmony, complimenting each other and their movie.

When I saw this film in theaters opening weekend I was mesmerized. I walked out, my head full of new viewpoints that I could incorporate into my coursework. I went back the very next day to try and catch more of the film, and to again experience the weird acid trip it offered.

Natural Born Killers spoke to me at a time in my life where I was already receptive to its message. I walked in expecting a road movie featuring mass murderers. I left thinking about media, and my own role in its creation.

But like Stone’s earlier film Wall Street, I feel the message of Natural Born Killers has been lost at best, or perverted at worst. Several instances of “copycat crimes” have appeared in the media, killers completely missing the point and, instead, are seemingly inspired by Mickey and Mallory Knox. It’s impossible to say if those acts would have been done without this film, but it’s a sad irony that a movie about the dangers of media violence then creates its own.

Yet every day when I look at the news, I feel that Natural Born Killers did not succeed in warning the media, or its consumers, about the impact of tabloid journalism. From Britney Spears’ head-shaving incident to Charlie Sheen’s “winning” display to even Robin Williams’ tragic suicide, the media is there to try and grab big ratings under the guise of informing the public.